The Freedom in Failure

Every South Asian family has that one child who has been selected as the great hope. The one who will drag them to a higher station in life. The one who will bring glory to the family. That child never asked for this; they just had the misfortune of showing slightly more promise in their youth, and now it is their cross to bear.

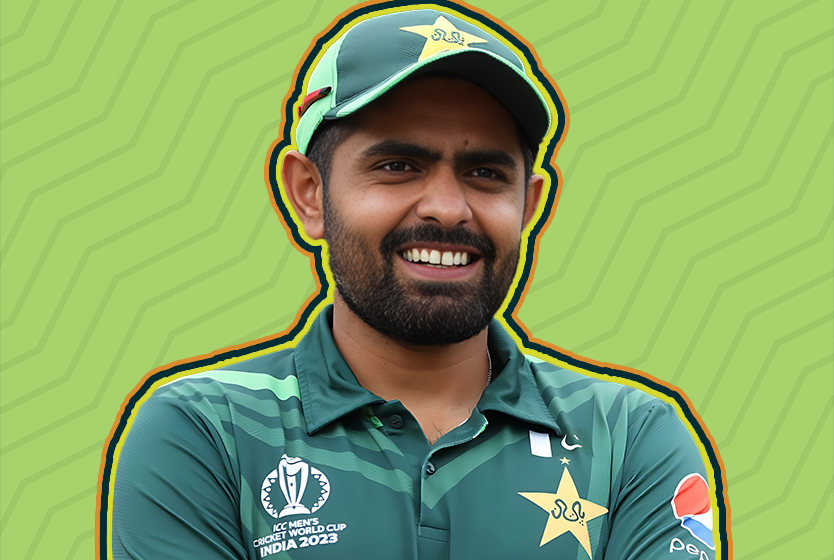

Now imagine that single South Asian family was a country of 230 million people, and that one child was Babar Azam. Since cricketing birth, he has been told he is destined to be great. He is the one who will drag Pakistan to the top. And to his credit, he was never reluctant to accept what was expected of him.

You could never call Babar a reluctant captain because this was, in his and everyone else’s mind, a natural progression. Pakistan never puts much thought into selecting a captain – from the Gali Mohalla teams to the national team, it is simple – the best player is the captain, and Babar was always the best player. Captaincy was what was expected and provided to him at every turn. In true Pakistan fashion, the actual acumen to captain was treated as optional.

When Babar was growing up, he would have been told four things:

- “You will play for Pakistan.”

- “You will bring glory on yourself while playing for Pakistan” – records, medals and awards.

- “You will captain Pakistan.”

- “You will bring glory to Pakistan” – trophies.

Looking back, he achieved 75% of that, but as any true South Asian family will tell you, anything less than an A is basically a fail. And now he will give up point number 3, too, so at this point, he’s no better than his other cousins.

The thing about that child is that you have to disappoint your family for the freedom to live your life. Disappoint them enough times, and eventually, they start negotiating down their expectations. It is no longer “be our World Cup-winning captain” and more just “be our best batsman of all time.” A few more disappointments, and he can negotiate it down to “our best batsman of the 21st century”. Failure brings disappointment; disappointment brings freedom from expectations. It is a slippery slope – somewhere down the slope is that blissful point of contentment with your lot in life, and it differs from child to child.

Babar is now free to be the best batsman he can be without worrying about which bowler to bowl. The pressure will always be there, and the expectations when he walks out to bat will remain. But now, he can run to long on and let someone else worry about why the opposition batsmen are batting longer than they should be.

“Your father loves you, Faramir; he will remember it before the end.”

The truth is that a cricketing country that remembers and loves cricketers for a single over they might have bowled will remember and cherish Babar when he is gone. He just needs to get through the career part of his career, and then he can sit on a panel with his friends and make disparaging comments while being defended by half of Twitter.

Ultimately, Babar is destined for so much more, and we have probably not seen the last of him as captain because when in doubt, Pakistan cricket will fall back to their base logic – the best player has to be captain because the rest can not be trusted to stick around. And perhaps that is his fate, to have the curse of immortality.

The curse of immortality has been touched upon in various forms of media. When you are young and death scares you, the prospect of immortality is tempting, but as you age, you come to terms with the fact that you will be around for all of time while others will fade around you, to be eternally alone. To be eternally blamed for what occurs because you will be the constant, and hence, the correlations will begin. Babar will probably see three generations of Pakistan’s cricketers in his single career, and he will likely captain all of them. His impact has already been felt by all; his nature of legacy is yet to be determined, but the existence of it is certain.

Goodbye, Captain Babar. Till we meet again.

Leave a Reply