Pakistan’s Nawaz-Shaped Hole

Truth to be told, all left-arm spinners look the same. Their action is the same short shimmy to the crease, a brief wave of the arms, and then the same ball on a length day after day. Sure, you will have your Zulfiqar Babars who opt for more theatrics, but it is purely limited to the action; the end result is what you would get from any other left-arm spinner.

It is thus difficult to judge which left-arm spinner is better than the other without a wider sample size. Because the main selling point for them is consistency, and consistency can only be established if it is allowed to be proven.

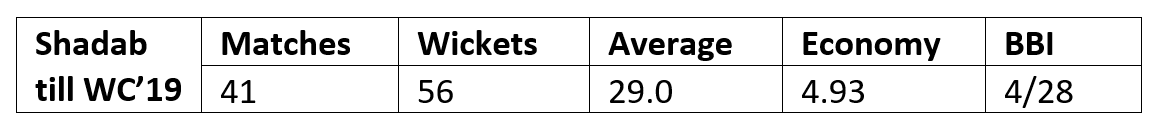

Pakistan’s spinners are a problem in ODIs; they have been a problem ever since the ICC decided Saeed Ajmal’s arm bent greater than 15 degrees. Since then, Pakistan have only seen one spinner average under 30 over an extended period (30+ matches) – Shadab Khan from debut to 15th Jul 2019.

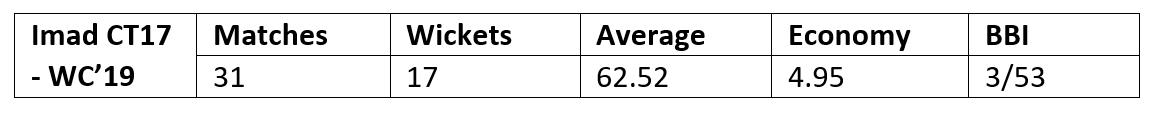

Pakistan’s 2019 WC squad had Shadab performing the lead spinner role, with Imad in the all-rounder role at Number 7. Imad was just expected to keep it tight and bowl 10 overs; getting wickets was not in his purview and rather a happy coincidence.

Post-2019 WC, Pakistan decided to dream bigger with the thinking that now Shadab was mature enough with the bat to perform the Number 7 role, an assertion that he has proven to be correct, and now was the time to enhance the side with a more attacking second spinner. But not willing to lose out on Imad’s economy in the quest for wickets, they turned to Mohammad Nawaz, who was considered a “better” spinner than Imad. With Nawaz a decent bat, they would not even lose out on Shadab’s batting at 8, as he could likely recreate Shadab’s batting output from debut to WC 2019.

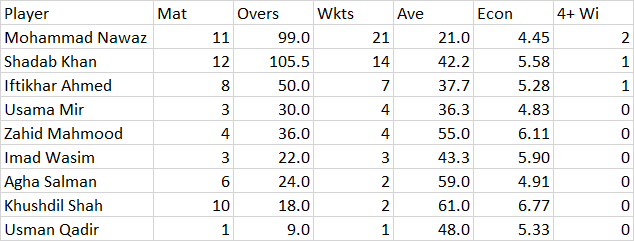

It is a move that seemingly paid off. Even with Shadab’s drop in bowling form due to various reasons, Nawaz took up the mantle of the main spinner of the side, providing breakthroughs in the middle overs when the team needed them. With the World Cup set to take place in India, where left-arm spinners would likely enjoy the conditions, Pakistan seemed set to go.

The only fear with having a left-arm spinner as one of your front-line five bowlers is that perhaps one day you may come up against a rampaging left-hander who just does not let them bowl. But even that fear was alleviated with not one but two off-spin all-rounders in your team, both of different styles, who could fill in the overs you might have otherwise lost.

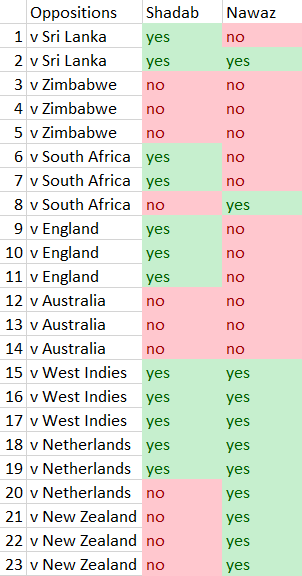

Until April 2023, Pakistan could seemingly dream of a bowling attack where both of their spinners could average under 30, a feat not achieved since 2013. Now, perhaps they were living in a state of delusion because their dreams were based on a smattering of ODIs played vs. mostly lower-ranked oppositions set months apart from each other. Pakistan did not play many ODIs anyway, but their seemingly first-choice spinners for the 2023 WC played even lesser, leading to an even smaller sample size to judge them off.

Shadab had played little over half of the ODIs leading up to the pre-WC preparation season; Nawaz had played under half, but at least he had played all 10 leading up to it. All the while, they had bowled together in only 6 games vs. the lowest most-ranked teams Pakistan faced in that period. If they had been available for even the Australia series in 2022, Pakistan could have either adequately judged their capabilities or they would have gained the confidence of the backroom staff of doing well against a decent opposition. Instead, Pakistan fielded a spin attack of Zahid Mahmood, Iftikhar Ahmed, and Khushdil Shah.

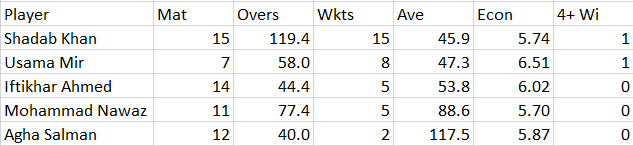

With Nawaz as their best spinner, averaging 21 since the 2019 WC, Pakistan were lulled into a state of comfort where they were not even as concerned with Shadab’s bowling form. They were confident that he could rediscover his 2017-19 bowling touch once he got more ODI bowling overs under his belt, with the caveat that he was still bowling better than Imad was in the 2017-19 period and thus could, just at worst, perform a better version of that role at the WC.

Being classically Pakistan, they failed to identify that the value that Nawaz brought to the bowling was two-fold. Yes, he was averaging 21, but his economy was also 4.45, ensuring Pakistan did not miss Imad’s stranglehold. Their solution to bolstering the spin bowling stocks was to bring in a leggie with a List A economy nearing 6, who could neither replace Shadab’s batting at 7, nor Nawaz’s control in the middle overs. In a nasty twist of fate, he also failed to take wickets in the middle overs, which was the main selling point for his inclusion. All the while, Pakistan had a spinner who was proven at the Test level with a List A economy of under 5 with similar domestic performances sitting on the sidelines.

Pakistan’s Plan A may have been unwise – it may have been a fool’s pipe dream – but it is their lack of foresight over their Plan B that may have signed their World Cup death warrant.

Leave a Reply