Pakistan and the Right to Dream Big…

Where does Pakistan stand in the T20 world and what are its T20 World Cup prospects?

Pakistan play a lot of T20s, they win more often than most, and they’ve reached the semi-finals or further in the 5/7 T20 World Cups that have taken place thus far. Yet, whenever a global T20 event seems to come around, they’re never really talked about as a side that could seriously challenge for the title. Why’s that?

They’ve had successful T20 sides in the past – from the 2009 T20 WC winning side that the likes of Afridi, Ajmal & Umar Gul starred in or the team led by Mickey Arthur that dominated in the UAE – but where does this current team rank?

Well, in the days that have followed their defeat in Asia Cup final to Sri Lanka, you’d be forgiven for thinking Pakistan had just lost ten matches in a row. It’s the passion of a nation that loves their cricket that causes this. At times, it can be a massive benefit; on other occasions, a hindrance.

The toxicity that follows a Pakistan defeat, particularly in a major tournament, is noticeable, both across social media to news outlets & commentary. Swarms of calls for ‘older’ players to be brought back into the setup, as their experience is needed, and any number of players, coaches, and tacticians will be blamed for defeats. In reality, Pakistan are still a quality T20 side. Despite the disappointing losses they’ve suffered in the World Cup semi-final and Asia Cup final over the last 12 months, only India can boast a better win percentage in T20s since the start of 2021. These losses, which are tough to take, are part of a journey for this team, and Pakistan fans & players alike will be hoping that journey leads to success on a global stage. Mistakes will be made along the way but provided they learn from those and don’t slip into their old ways, Pakistan cricket is heading in the right direction.

Asia Cup review

As I mentioned earlier, it was a disappointing outcome for Pakistan to lose in the final against Sri Lanka. However, is too much emphasis being placed on one result? If they had beaten Sri Lanka and won the Asia Cup, it would’ve been seen as a resounding success, whereas losing that final has prompted chaos and calls for various players to be replaced in the XI. In reality, it probably falls somewhere in between.

Of the six games Pakistan played in the Asia Cup, they won three, one of which was against Hong Kong. This isn’t a great return, but considering the form of Babar and the fact that they were without Shaheen Afridi, it wasn’t disastrous. Had they won the final, 4/6 wins would’ve been respectable, but it could’ve papered over some cracks in their XI. In some cases, this result might be a blessing in disguise, depending on what the next move from the PCB is.

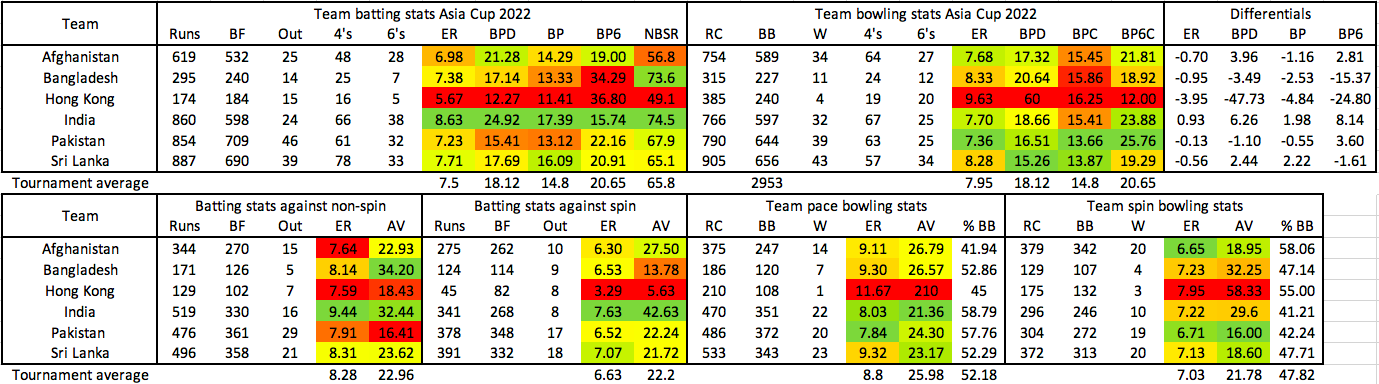

Stats from the Asia Cup:

The batting was the root cause of most of their issues throughout the tournament and considering they picked an XI to fit an extra batter into the side, this is a huge issue. Babar and Rizwan took the brunt of the blame for their performances. Babar just struggled more generally, and while Rizwan got some decent scores, he couldn’t accelerate. The issue was further compounded by Fakhar Zaman having a poor tournament managing only 96 runs in six innings (53 of which came against Hong Kong) at a strike rate of under 110.

The sluggish and poor stats from the top order, which often left them behind the eight-ball, doesn’t completely excuse the performances of the middle/lower order, though. They were often left with a lot to do but didn’t really get close to completing any of that. In fact, it was probably Shadab Khan & Mohammad Nawaz, when they were promoted up the order, that staked the best claim for a middle-order spot, with Iftikhar Ahmed, Khushdil Shah, and Asif Ali all having below-par tournaments.

What went well?

If there weren’t many positives from a batting point of view, there certainly were from a bowling perspective. Whether you look at the pace bowlers or spinners, they were generally superb throughout the tournament. The Pakistani pacers were the most economical in the tournament, and the spinners could only be bettered by the Afghanistan spinners, which mostly consisted of Rashid Khan and Mujeeb – there’s no shame in finishing second-best to them. Their spinners did carry the greatest wicket-taking threat, finishing with a bowling average of 16 – Shadab & Nawaz were superb with the ball.

A particularly pleasing aspect of their performances would’ve been the powerplay bowling. In the absence of Shaheen, Pakistan were counting on Naseem Shah to be able to have an immediate impact at the international level and Rauf to show greater versatility than he’s had to exhibit in previous T20Is. Both stepped and formed a potent new-ball attack that’ll only get stronger once Shaheen returns. In total, Pakistan managed to take 13 powerplay wickets this tournament while having the lowest economy rate and best bowling average. Of the 13 wickets taken, 10 of them came from the bowling of Naseem & Rauf. To do that without one of, if not the best powerplay bowlers in the world indicates great strength in depth.

Overall, there were definitely some big positives to take from the Asia Cup for Pakistan, though they probably came out of the tournament with more questions than answers. I did like how they eventually showed signs of being more flexible with their batting order, but the top-order approach/struggles leave valid concerns going forward. I also didn’t like or understand the rationale behind batting Iftikhar in the middle order, often at number 4. It felt like they had to shoe-horn him into the team. Selecting Haider Ali or consistently batting Shadab there would’ve been a better option, in my opinion.

What’s next for Pakistan?

The T20 World Cup in Australia is on the horizon, with their first group game (which is against India) taking place on October 23rd. However, before that, Pakistan have a multitude of T20 games to play in the coming month, including the remainder of the T20 series against England, followed by a tri-series with New Zealand & Bangladesh in New Zealand, and finally, two World Cup warm-up matches against England & Afghanistan.

Although the World Cup is so close, there are still plenty of games to experiment, fine-tune, and establish their preferred XI, though most of that should be fairly settled by now anyway. These games will be important for some of their batters to regain some confidence ahead of the World Cup, after a tough Asia Cup. The conditions in Pakistan & then New Zealand & Australia should be much easier for batting than the ones we saw in the Asia Cup. We’ve already seen that Babar & Rizwan have been beneficiaries of this in the first four matches of the series against England, scoring almost 450 runs between them so far.

This is the squad they’re using for that series:

There weren’t really any major surprises, though it’s a slightly larger squad than normal, so we get to see a few newcomers to the setup. Whether they’ll feature or not is a different question. Shaheen Afridi misses out as he continues his rehabilitation from his knee injury, while Fakhar Zaman is a fresh injury concern and also misses out.

The two fresh faces to the squad that haven’t been included in previous series are Amir Jamal & Abrar Ahmed, who have both impressed in domestic cricket recently. Amir Jamal is a lower-order hitter that provides a bowling option, and he boasts an impressive strike rate of 194 in the NT20 Cup this year. However, he’s probably slightly fortunate to have been selected after only one standout NT20 campaign. Meanwhile, Abrar Ahmed is a leg-spinner who has always been fairly highly rated; however, he seems to have kicked on this year. Firstly, he did well in the Kashmir Premier League, finishing with the lowest economy rate, and then took 10 wickets in the NT20 Cup this season. There could be chances for him to establish himself as the backup wrist spinner to Shadab, given the inconsistencies of Usman Qadir.

It’s important that these games still have some sort of continuity in terms of the selections that are made. You don’t want to get into the business of swapping the XI on a game-by-game basis. However, it’s equally important that rotation occurs, particularly for the fast bowlers. This is the main weapon for Pakistan; they can’t afford any more injuries in this regard, and it would drastically hamper their World Cup preparations. As of now, they haven’t really rotated as much as I would’ve liked, with Rauf playing all four matches, which is possibly an unnecessary risk, in my opinion.

In order to get the most out of these remaining games, Pakistan need to be prepared to experiment with things within their XI and perhaps be more flexible than they have been in the past and even in this series so far. Due to injury issues with Shadab and Naseem Shah, as well as the continued absence of Shaheen Afridi, we haven’t really seen something that’s too close to Pakistan’s strongest XI. It would be nice in the remaining games if we got to see a stronger Pakistan XI (minus Shaheen), but obviously, players shouldn’t be rushed back from injuries, even if they’re only minor.

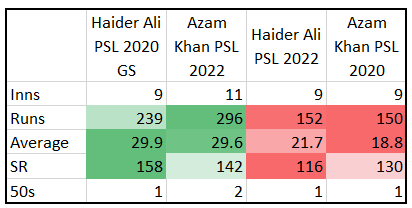

In my opinion, this is the strongest Pakistan XI when Shaheen isn’t available, though it’s important that the batting order remains fluid. Shan Masood over Fakhar would obviously be the biggest debate. However, with Fakhar out injured, it’s a good opportunity for Shan to stake his claim ahead of the World Cup.

As for the bowling, the first-choice bowling lineup remains the same, with Shaheen still out on the sidelines. An argument could be made for Mohammad Wasim jr to come into the side in place of Hasnain; Wasim jr was initially included in the Asia Cup squad before his injury, and Hasnain wasn’t. Therefore theoretically, Wasim jr should be ahead in the pecking order. However, I’m not sure that’ll be the case, and in any case, there’s a chance Wasim jr may have been included for his batting value and not just his bowling. Currently, I don’t think he’s capable of being a bowler in a 3-man pace attack, so I’d pick Hasnain ahead of him. This may lead to Pakistan experimenting at times if they want to give Wasim jr some game time, potentially resulting in a 4-man pace attack, with one of the batters dropping out of the XI. That’s something that could be a viable option in Australia, though I’m not necessarily a fan of it.

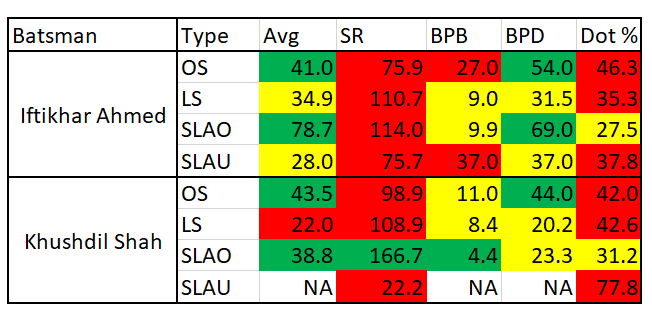

This means the final selection debate is over whether they pick Khushdil or Iftikhar; for me, there’s only room for one of them in the XI. I didn’t like how they shoe-horned Iftikhar in at 4 in the Asia Cup, and I’d rather they give matches to Haider Ali in that position, even if I don’t think that’s his optimal position long-term. This means at least one of the two players mentioned has to drop out of the XI; who should that be? It’s not an easy call so let’s compare them.

Khushdil vs. Iftikhar

To compare Khushdil and Iftikhar, you first have to understand how similar they are. Both of them are not intrinsically T20 batsmen; they are List A batsmen. A majority of their limited-overs success has come in List A tournaments where they are essentially high-yield anchors. They did not play that 5 or 6 roles for their respective teams; that role would be handed to the team wicket-keeper or all-rounder, regardless of the fact that none of them may be suited to the roles assigned because “cricketing logic” dictates that you have your five batsmen, then your wicket-keeper, the all-rounder, and then finally the four bowlers. Khushdil and Iftikhar would walk out at number 4 for their teams; they would be their team’s premium batsmen because Pakistan’s List A competitions are the most neglected of the cricketing calendar. There they would face all sorts of bowling, play till the end, and then tee off. It is a method that has brought them great success, as their List A records indicate.

Most T20 games in Pakistan were played with a similar philosophy of “lamba khelna.” It was only when the PSL came along that the discourse and ideas around T20 cricket began to change. The game no longer became about getting to the last five overs but actually utilizing the entire twenty. Khushdil and Iftikhar were promoted to PSL level, where they had some success, but they were always attempting to adapt their List A style to T20s.

Both of them are among the best hitters of pace in the country; in fact, Khushdil, in particular, has the highest SR vs. 140+ pace of any Pakistani batsmen with a decent average to boot. It is such numbers that could lead them to be classified as “pace hitters” because, after all, they are hitting pace bowlers. But they are not pace hitters; rather, they are “death hitters.” They only seem to actively attack when it comes down to the last four or five overs. Before that, it is all about getting to those death overs, and thus, they have earned this reputation as slow starters. It means that if Pakistan were to currently utilize them, they would have to be allowed to settle before launching. Alternatively, they can be thrust into a situation where they are required to attack from ball one.

It is here where the vulnerability vs. spin becomes a greater issue because if you send them early to get settled, then you are basically taking a loan in hopes of a greater return. In the hope that that 8 off 10 will turn into 44 off 25 by the end. The issue is that by sending them early, you may be actively exposing them to what they are most vulnerable to. The question then becomes: How vulnerable are they really?

Khushdil is decidedly more vulnerable overall, but he has a positive matchup vs. SLA. Meanwhile, Iftikhar is not as vulnerable, but there does not seem to exist a spin type that he feels comfortable attacking. But vulnerability may not be as big of a problem as the strike rate and dot ball %. The strike rate naturally indicates that they can be kept quiet by employing spin. This can be overcome by team planning so that the set batsman already at the crease knows he has to give Khushdil/Iftikhar time to settle. He then actively attacks the bowling, so the team as a whole does not slow down because of them. Unfortunately, this has not happened so far because either the batsman at the other end is equally vulnerable, new to the crease, or is an anchor who is also looking to play till the end. But nevertheless, if Pakistan do manage to concoct such a strategy, they will have to deal with that dot %, which indicates that not only does spin keep Khushdil/Iftikhar quiet but actually leaves them stuck at one end. A single to get down to the other end is a batsman’s best weapon against a negative matchup, but Khushdil/Iftikhar do not seem to have that in their armories.

So ultimately, Pakistan can play them in two positions – at number 5 with an entry point around the 14th over, two overs to settle before the launch, or at number 7 when they walk in around the 18th and are expected to go from ball one. The number 5 strategy is fraught with risk on the occasions that they depart before launching, and the number 7 strategy is one where their impact may be limited. Nevertheless, if you were to send one at 5, you would send the guy who is less likely to get out. As of now, that seems to be Iftikhar, who has a superior average vs. spin, and even in List A, cricket averages 50 to Khushdil’s 40. A case for Khushdil in that role would be that he actually has a better middle-overs record than Iftikhar in T20s, has a higher upside, and has one positive spin matchup.

The higher upside can be indicated by their strike rates after a certain number of balls are faced. The approaches are similar, but Khushdil seems to be more destructive when set, striking at 11+ runs per over, while Iftikhar goes at around 10 to the over.

When it comes to performances at the higher levels, there does not seem much to separate the two. Khushdil has better performances at the PSL level, perhaps down to Multan’s better utilization of him, while Iftikhar has been middling at the PSL level but has a better international record than Khushdil. Given a choice, one should usually trust PSL records more because T20 International records are a result of a few innings that may be months apart in different situations. However, Pakistan does not think like that, and ultimately Iftikhar is likely to win this tussle because he has proven to be more trustworthy in the eyes of the management.

The other factor in play that pushes Iftikhar’s case is his back foot game which is in better shape than the likes of Khushdil and Asif. Add that to the fact that he was one of two batsmen for Pakistan to cross 40 in T20Is on their horror tour of Australia in 2019. And finally, there is the factor of his off-spin, which in theory is a nice complement to the away spin of Nawaz and Shadab, both of whom are likely to play all the games at the World Cup. Iftikhar has now bowled over 20 overs in T20Is and goes at a decent economy of 7.18.

Ultimately, the bottom line is that Khushdil is a better T20 batsman than Iftikhar and will perhaps remain Pakistan’s Asif backup/replacement for a long time, considering the dearth of death hitters in Pakistan’s system. But as of now, Iftikhar will play ahead of him, a final swansong for Pakistan domestic’s finest. He is unlikely to feature in any of the international sides after this World Cup, and it will be his final shot to go down as more than the guy who “looks” older than he actually is.

Assessing Pakistan

Now onto the crux of the article. Where do Pakistan stand ahead of the T20 World Cup?

To put it simply, I think they’re in a decent enough position. The way they performed in the Asia Cup wasn’t ideal, but it wasn’t enough of a reason to panic. More crucially, the Pakistan selectors didn’t panic, and they’ve largely picked the squad that many would’ve wanted or expected:

The big omission is undoubtedly Fakhar Zaman, who suffered an injury, but I suspect his place would’ve been under pressure anyway. He has been replaced in the squad by Shan Masood. Other than that, it’s pretty much as expected for Pakistan. There could be an argument that Usman Qadir is slightly fortunate to keep hold of his place in the squad. Shahnawaz Dahani & Mohammad Haris are two positive inclusions amongst the traveling reserves.

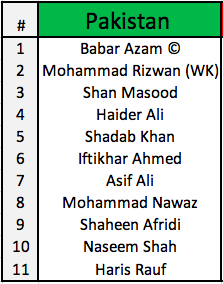

Fakhar Zaman vs. Shan Masood

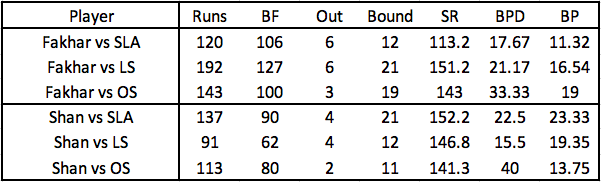

There’s no doubt that the decision to pick Shan Masood ahead of Fakhar Zaman has split opinions in Pakistan. You can certainly see why; Fakhar has been a regular in both white-ball formats for years, while Shan only has five ODI appearances to his name, has a middling record in T20s, and also turns 33 next month. Added to that, Fakhar had his best-ever PSL earlier this year, in terms of both strike rate and average, hitting 592 runs in his 13 innings, at a strike rate of over 150. By looking at this, it would seem like an easy decision between the two, right?

Well, that’s not exactly the case. Despite a glowing PSL earlier this year, Fakhar’s performances for Pakistan have been sub-standard. In T20Is since the start of 2019, Fakhar has averaged 17.4, with a strike rate of 119, across a sample size of 40 innings. While it’s true many of these innings have come outside of his preferred opening position, I’m not sure it’s unreasonable to expect much better than the numbers he has provided in the last few years. Of the 22 innings he has played at number 3, Fakhar has managed an average of 23 and a strike rate of 117. While many of these games have come in tough conditions but again, I’d expect more.

By contrast, Shan is perhaps on more of an upwards curve in T20s, though he probably doesn’t have as much upside in the format as Fakhar, on a good day, has. The problem is that those good days have been few and far between in Pakistan colors. The image of an in-form Fakhar is a significantly better T20 player than Shan Masood. However, I’m not sure that the current version is.

When comparing them, it’s important to consider what’s going to be required of them in the role they’re likely to play for Pakistan. Batting at 3 for Pakistan is very different from batting at 3 in most T20 teams due to the solidarity of Babar & Rizwan at the top of the order. Particularly important stats for the role of the number 3 in the Pakistan side will be starting strike rates, willingness to attack spin matchups, and overall quality of their game against spin. As such, a player with good numbers overall but who relies on pace hitting wouldn’t be desirable for this team.

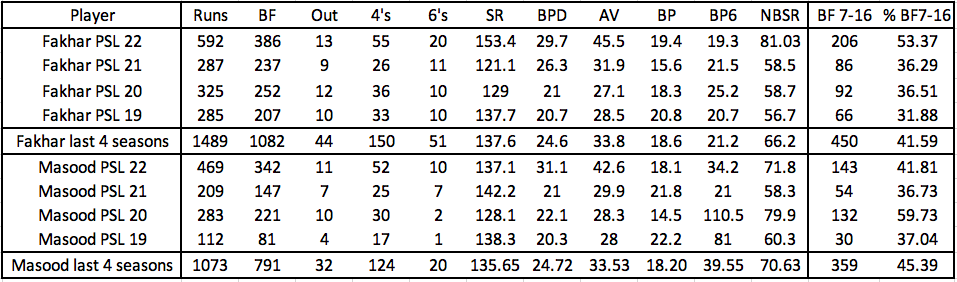

Firstly, if we look at their overall PSL records over the last four seasons:

We can see that their numbers are very similar, with both of them averaging 33 and striking in the mid-high 130s. Fakhar has exclusively batted as an opener in the PSL, while Shan had a stint at 3 for eight innings in PSL 2020, averaging 28 and striking at 130. The one clear difference between the two is their six-hitting prowess; Fakhar has 31 more sixes than Shan in the past four PSL seasons and, on average, hits a six almost twice as regularly as him. Just from watching the two, you can clearly see that Fakhar is the more powerful striker of a ball. However, it does seem to be something that Shan is working on, hitting 17 out of his 20 career PSL sixes in the last two seasons. There’s an argument that Fakhar has the most upside, and that looks to be true; his PSL 22 season was not only the most runs any of them have managed in an individual season but also the quickest any of them have scored runs in an individual season. It was a fantastic season, though I’m slightly skeptical over how repeatable it is, given the big increase in non-boundary strike rate, in comparison to previous seasons. His NBSR before that had regularly been in the high 50s, which is what we’d expect based on his NBSR of 59 for Pakistan & 60 in the NT20 Cup.

Both haven’t played for the same PSL side in the last four seasons, which helps when we want to cover for potential differences in team batting approaches. However, Multan and Lahore have had similar scoring rates anyway, with Lahore scoring at 7.98 RPO vs. 8.04 RPO for Multan in the previous four PSL seasons.

Facing spin

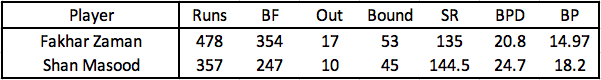

Onto the more important stats, if we look at their PSL numbers against spin:

Both have above-average numbers against spin in the PSL, though Shan Masood does seem to be superior and more attacking against spin overall, evident by the higher boundary percentage. However, it’s worth noting that Multan, who Shan Masood plays for, are generally very matchup savvy and were perhaps more forward-thinking than most PSL teams in that regard. The boundary percentages aren’t weighted for sixes, so the gap would be slightly closer but not significantly because although Fakhar is generally a much better six-hitter, there isn’t too much of a difference between their balls per sixes hit against spin. If we look at their performances vs. individual bowling types:

Once again, it looks like Shan is more willing to attack SLA while also having a higher boundary percentage against leg-spin. Both have impressive numbers against off-spin, considering it’s not their matchup, though Fakhar’s numbers haven’t translated across to the international level. If Shan can maintain that level of proactiveness against off-spin for the national side, it’ll make it very difficult for opposing sides to get through cheap overs of off-spin against them, with Babar/Rizwan also showing they’re more willing to take it on in the T20 series against England.

While Fakhar has been a decent player of spin in the PSL, those numbers are in stark contrast to his against spin in T20Is, where he’s generally struggled, striking at 109 and averaging 18, though quite a few of those games have come in the UAE, where conditions are particularly tough for facing spin-bowling.

Starting strike rates

If we look at the starting strike rates for both, it’s clear that Fakhar has been the more fluent starter in the PSL, striking at 127 in his first ten balls vs. 104 (last four seasons), though Shan is the slightly more reliable starter, averaging 50 vs. the 41 that Fakhar averages in his first ten balls. Once again, though, it does seem to be something Shan has been working on as he strives to become a more viable option in T20 cricket, striking at 118 in his first ten balls last season, in comparison to 95 in the previous three seasons. In his stint with Derbyshire this year, it was just shy of 130 in the T20 Blast.

I guess what will probably be most important is the rate at which they can start vs. spin, as that’s going to be the most likely role for Pakistan. While this data is potentially a little noisy because most of it would have come when they’ve been opening, it’s probably still worth considering. When facing spin in their first 10 balls of an innings, the two have very similar strike rates, with 107 for Fakhar vs. 109 for Shan (All T20s since 2020). However, there is a bigger difference when looking at spin in the first 15 balls, with 108 for Fakhar vs. 121 for Shan. This suggests that neither is comfortable attacking spin from ball one, but Shan will start doing it quicker than Fakhar.

Finally, how do they compare when trying to accelerate against pace later in the innings?

This is data from the last ‘third’ of a T20 innings (overs 14-20), and there’s no doubting which player is most effective during the phase of the game against pace. Perhaps, it isn’t too surprising either. Both have a similar average, which isn’t really too relevant at this point in an innings, and Fakhar is far superior when it comes to strike rate, scoring boundaries, and hitting sixes. Shan Masood could be as aggressive as he wants, and I’m still not sure he’d get too close to Fakhar in this regard. There’s just a notable difference between the power of each player that clearly emerges when they’re facing pace bowling.

Summary/overall thoughts on the debate

To summarise this selection debate, I think it’s a very difficult decision for Pakistan to make, and it definitely isn’t as black & white as many of Fakhar’s fans would have you believe. We need to give credit to Fakhar for his willingness to bat in any position for Pakistan over the last few years, with only a small percentage of his innings coming in his optimal position. However, that shouldn’t be a reason to keep him in the team, as I’m sure many players in Pakistan would be willing to sacrifice batting in their natural position to play for Pakistan rather than not being involved at all.

There’s also the other argument that if Pakistan have stuck with Fakhar for this long, through various form slumps, why would they not continue to back him for another 2-3 months? Nevertheless, at what point do you say enough is enough? While 40 T20 innings wouldn’t be considered a massive sample size, in T20Is, it certainly is. The 45 T20Is that Fakhar has played for Pakistan since 2019 is more than the majority of players will play in their career – Almost 3050 players have played a T20I since their introduction in 2005, and only 155 have played more than 45 in their careers (data from Cricinfo). In other words, only 5% of players have appeared more times in their T20I careers than Fakhar has for Pakistan since 2019. Of course, with an ever-increasing amount of T20Is being played and plenty of those 3050 players having ongoing careers, they’ll likely add to their current appearance tallies, but it gives a perspective of how many chances Fakhar has been given.

Pakistan has given Fakhar the longest rope they possibly could without having to address the issue. Now a point has come where they’ve had to do something, regardless of the seriousness of his current injury. I don’t think having Fakhar as a guaranteed starter in the XI was possible anymore; they at least needed to give him some challengers for his position. My issue with the Pakistan selectors/management isn’t that they’ve made this decision to seemingly replace Fakhar but that there seemed to have been a lack of planning in advance for this situation.

There was no contingency plan in place; it always felt like they were just assuming that Fakhar would start providing a better output eventually. Well, 40 games have passed, and now they’re looking for a quick fix ahead of a T20 WC. Haider and Azam Khan should’ve been gently budded in as middle-order players over the last 18-24 months, especially after the retirement of Mohammad Hafeez and the non-selection of Shoaib Malik. For reference, Haider & Azam have played 47% and 11% of the possible T20 internationals since their debuts. More effort has been made with Haider, though ideally, both would’ve played a bit more often. The issue for Pakistan is that they haven’t actually played that many T20Is since the World Cup last year (14 before the England series), which was when Hafeez and Malik were removed as regulars from the side.

So there’s almost been an element of rushing to find a Fakhar replacement because of the reluctance to give adequate opportunities to Haider & Azam over the last two years. This paves the way for Shan Masood. Whether he was asked to or willing to, or maybe both, he opted to bat in the middle order in the NT20 Cup this year. Considering he’s mainly opened in his T20 career thus far, this indicated his willingness to bat in the middle order if a spot opened up in the national team. Despite not having a particularly great campaign (average 30, SR 128), he’s been picked and will likely get opportunities in the coming matches. Can he offer a long-term solution? I’m not sure; at the age of 32, his time is probably limited, but there’s scope for him to be a good stop-gap option until the likes of Haider and Azam are fully established on the international stage.

As for my opinion on the debate, I think if the role is predominantly about batting at 3 and provided the batting order stays fluid, then Shan, at the very least, deserves a run in the side. Which he’ll get/is getting currently due to the injury Fakhar has suffered. If Shan impresses in the matches before the World Cup, he should maintain his spot in the team. It’s a case of unfortunate timing for Fakhar, both with the injury and that his poor form of late has coincided with playing lots of matches in tougher conditions, though his returns have been underwhelming for a while in T20Is for Pakistan.

Evidently, Shan Masood is an improving T20 player, and the fact that there’s even a consideration that he might become a regular in the Pakistan XI is a testament to his progress. His willingness to adapt and play unselfishly has earned him this opportunity; now, it’s a question of whether he can continue playing in the same fashion under the pressures of representing his country, knowing he’s playing for his place in the side. Evidence from his first three innings in a Pakistan shirt (T20s) suggests yes, with Shan playing an attacking shot to roughly 86% of his deliveries, which is roughly 9% higher than the series average so far. What he may lack in raw suitability to the T20 game, he makes up for with his approach. Yet, it’s arguable that two of the three innings he’s played have been negative impact, somewhat canceling out his excellent 65 (40)* in a losing cause in the third match of the series. And therein lies the problem with Shan; if you aren’t going to be flexible with his role and, in some cases, possibly not use him, you’re almost setting him up to fail if he bats at 3 or 4 no matter the situation. No matter how positive his approach is, it won’t compensate for the fact that there are much better players in the Pakistan side than him for certain situations in a T20 innings.

With that said, there is a role that would suit him in the Pakistan team, and as of right now, he might be the best option for it currently.

In conclusion, if Pakistan are looking for a number 3 and are willing to be flexible with the batting order, then Shan Masood could be the guy they’re after. However, if they want a number 4, with a more fixed batting order, then Fakhar would likely be a better option, regardless of his form.

Age Profile – Competitive now, but the future looks even more promising

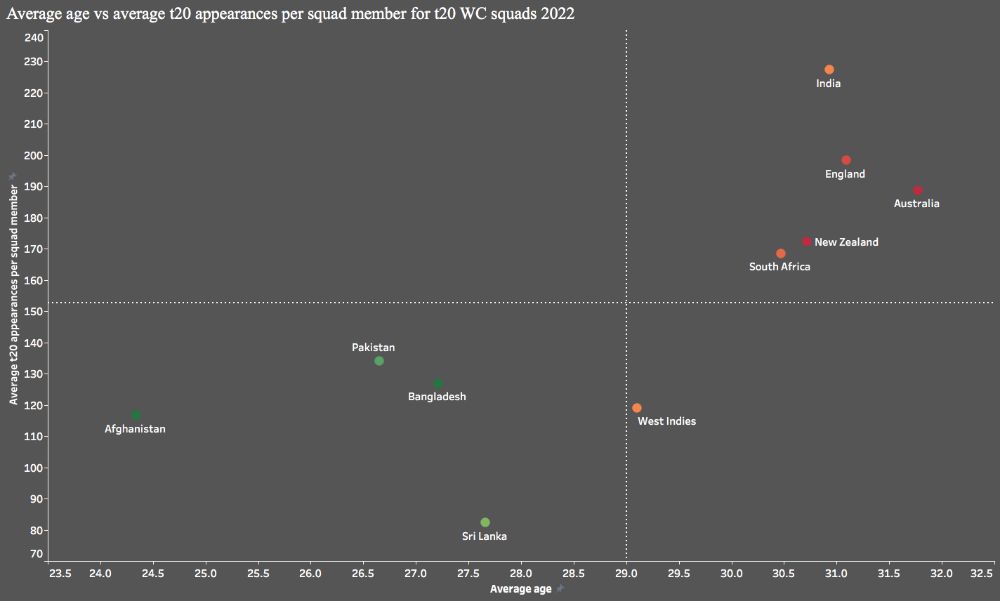

The Pakistan squad definitely isn’t perfect, and they might have periods of poorer performances. However, one major positive is the age profile of the squad. Compared to a lot of other ‘bigger’ nations, Pakistan are much younger and have far more room to develop:

Afghanistan are the only side amongst the top 10 nations to have named a 15-man T20 WC squad with a younger average age than Pakistan. Alongside that, their average age is almost 2.5 years below the tournament average. They rank 6th (out of the top 10 ranked sides) in terms of average number of T20I appearances per squad member, but most of the players in their starting XI have played enough cricket in high-pressure scenarios for this to not be an issue.

In any case, T20Is aren’t the be-all and end-all; many players play just as much cricket in T20 leagues nowadays:

Note – The color of the dot indicates the number of players under the tournament average age. New Zealand & Australia are the lowest (3), and Bangladesh & Afghanistan are the highest (13).

Strengths and Weaknesses

Strategic weaknesses

Of the national sides out there, I’d say Pakistan are one of the sides with more obvious strengths and weaknesses than most, and that’s not only reflected in their T20 World Cup squad but also more generally in domestic cricket.

Before looking at overall stats for Pakistan in T20s, one area in which they’ve generally struggled is batting 1st vs. chasing in T20s. Since the start of 2021, of the 33 games Pakistan have played, they’ve batted first 17 times and won 10 of those, whereas they’ve chased 16 teams and won 13 times. The sample sizes are fairly small, but there’s a clear bias towards chasing. If we go back to 2020, they won a further 6/6 games chasing and only 1/4 setting a target. So, the question is, how does a team with a more conservative batting approach get better at batting first?

Firstly, as with most things in life, practice is important. There are plenty of matches before the T20 World Cup, and my belief is that Pakistan should opt to bat first in the majority of games where they’ve won the toss. They’ve been reluctant to do this in the past. How can you expect to improve if you don’t actively seek to practice something?

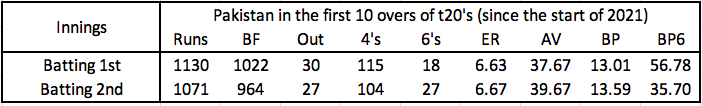

Does their intent need to improve when batting first? A common misconception is that Pakistan are more aggressive at the start of their innings when batting 2nd, as opposed to batting first, when that isn’t really true:

We can see that their scoring rates in the first 10 overs of an innings have been remarkably similar in both the 1st and 2nd innings. However, what does change is the range of scores they achieve:

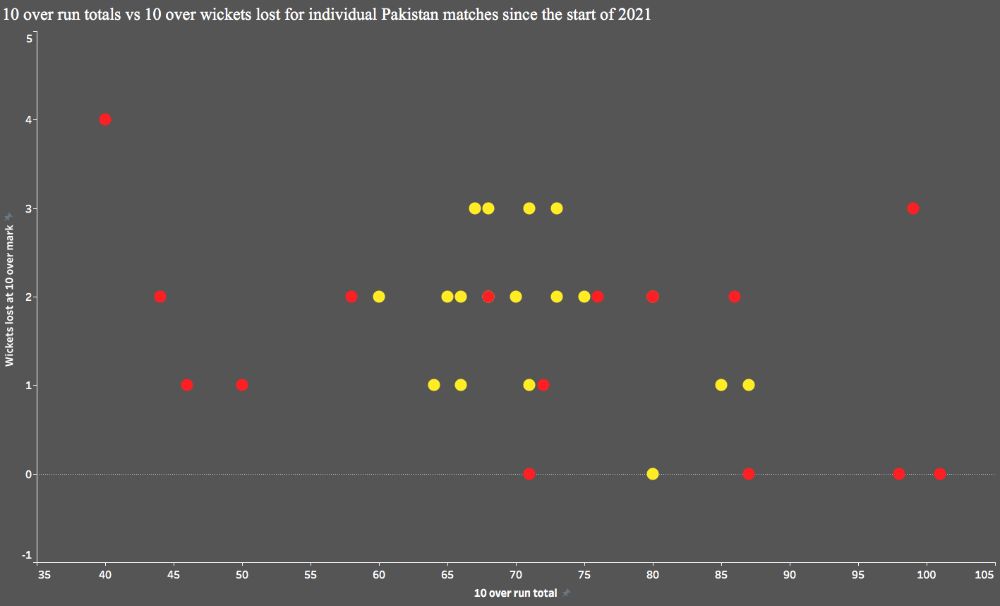

Note – Yellow dots indicate occasions where they’ve batted first; red dots = batting 2nd. Data includes games up until 22nd September 2022.

The same graph as above with lines to indicate average first 10-over scores/wickets lost when batting 1st & 2nd:

Note – This includes extras, hence the slight difference from the averages shown in the mini-table before these graphs.

Again, the first thing you notice is how similar the average lines are when they’re batting 1st; compared to batting 2nd, the average score is generally very similar. Is there a ceiling to how quickly Babar/Rizwan can score on a regular basis? The range for the dots in the 2nd innings compared to the first innings suggests that this isn’t the case. The yellow dots are much less spread out, which suggests they’re a far more versatile team when batting 2nd and probably explains why they’re such a formidable outfit when chasing. It looks like there’s a much more rigid plan when batting first, and they’re looking to reach a preconceived idea of what they believe to be a par score rather than adapting to conditions or capitalizing on strong positions they find themselves in. Out of the 18 times where they’ve batted first, they’ve scored between 60-75 runs in the first 10 overs on 15 of those occasions. By contrast, when batting 2nd, they’ve only scored between 60-75 on three occasions. There’s a far greater range when batting 2nd, and it largely varies depending on the target they’re chasing:

There’s generally a fairly strong correlation between the target they’re chasing and the rate at which they decide to start their first 10 overs. It’s also worth noting that most of those extremely low 10-over totals came against Bangladesh in tough batting conditions. I doubt any team would plan to start that slowly, irrespective of the total they’re chasing. It begs the question, why is there seemingly such a rigid plan in place when batting first?

You could argue that their strength is also their weakness in this sense. Pakistan have basically always been a stronger bowling side in T20s, and it’s no different now. Because of this, it may lead to them being less ambitious when it comes to setting an above-par score. They’ll always have the fallback of ‘we’ll back our bowlers to defend it.’ Indeed, many in this Pakistan side made their first strides in international T20Is under a Mickey Arthur-led side that did just that, regularly batting first and defending whatever target was set. However, that was generally in very different conditions in the UAE. I’m not sure the same approach is as viable now that they’re back playing their home matches in Pakistan and with the advancement of T20 batting over the last few years.

There’s also the possibility that they don’t really trust their middle order, and that would be valid, though this is a fairly contentious topic when discussing Pakistan batting performances. Some will argue that Babar/Rizwan have to be conservative due to the middle order failings, while others will argue that the middle order fails because Babar/Rizwan don’t score quickly/take enough risks earlier on in their innings. In reality, it probably lies somewhere in between, though I’m certainly closer to siding with Babar & Rizwan on this debate.

Ultimately, it’s a balance between conservatism and aggression that Pakistan will continue to chase and may never find. They don’t need to strive for 200 every game, but equally, they can’t settle for scores around the 140-150 mark. If they can consistently get scores in the region of 165-170, they’ll be in the game with their bowling attack more often than not.

Rigid bowling plans

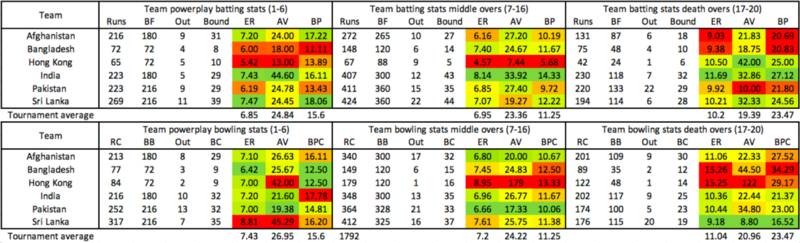

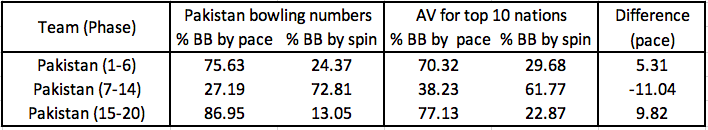

If you’re active on Twitter during a Pakistan T20 game, you’ll often see jokes referring to the bowling plans they have in place and that they don’t really change, regardless of situations/conditions. The 6/8/6 is often talked about in reference to them bowling six overs of pace, followed by eight overs of spin & then six overs of pace again. Is that the case and are their plans more rigid than other T20 nations?

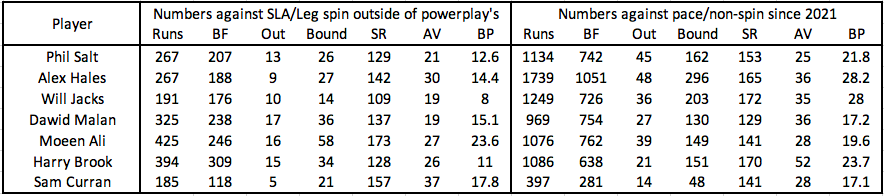

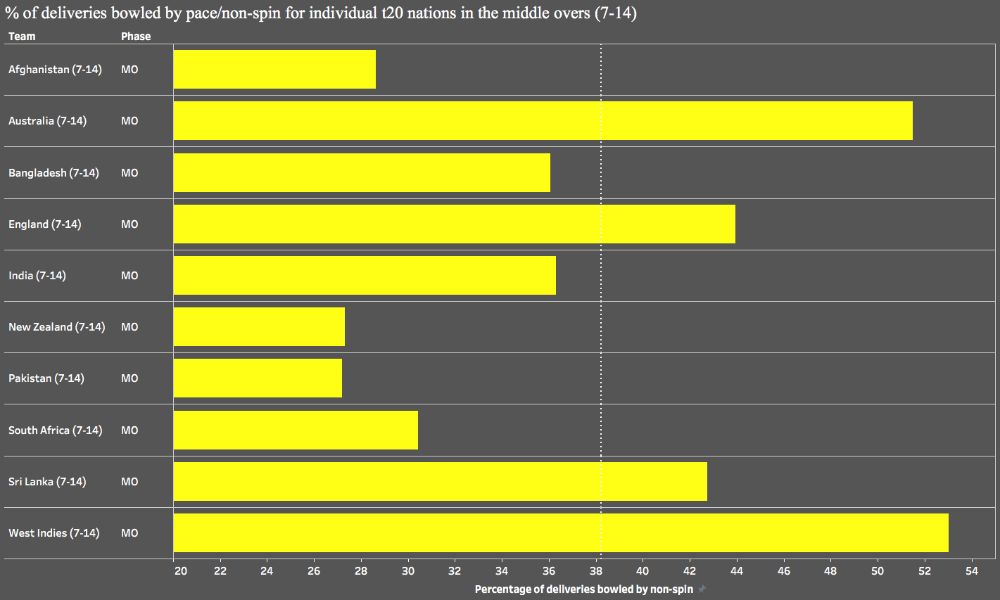

I think there’s definitely evidence to suggest that Pakistan aren’t flexible enough with their bowling plans, and many would argue we’ve even seen cases of that in the first few games of the T20 series against England. One such example would be their continued ploy to bowl spin through the middle, in the aforementioned 7-14 over phase (referring to the ‘8 overs’ of spin), even when Ben Duckett has been at the crease, who is known to be a much better player of spin, especially SLA/leg-spin, which is what Pakistan have been bowling at him through Qadir & Nawaz.

Duckett averages 33 and strikes at 167 against these bowling types since the start of 2019, in comparison to 31 & 134 against non-spin/pace bowling in the same time frame. Despite that, Pakistan have almost exclusively bowled spin (Nawaz & Qadir) to Duckett in that 7-14 over phase, with 51 of the 61 deliveries he’s faced between these overs coming from those two bowlers. They’ve paid for it as well, with Duckett taking 92 runs from those deliveries, including 14 fours. He’s been allowed to sweep until his heart’s content, but why? With such an obvious discrepancy in numbers, the pace bowlers simply have to be introduced earlier than they have been. The most obvious argument for this would be that Duckett has often been batting with RHBs that have a preference for pace on the ball. While this is true, I feel Pakistan need to be braver. Pace bowlers are very much the strong suit for Pakistan, even more so in this series so far, with Qadir stepping in for Shadab. If you aren’t willing to back one of the biggest assets in your side, then what’s the point? If you can get Duckett early on with pace, the spinners become more threatening later, with Moeen being the main issue they’d have to contend with after that. That’s not always the easiest, but I’d rather that than having to bowl pace to Harry Brook/Livingstone (when he plays) or a set Salt, Hales, or Jacks.

If you bring pace on for Duckett early in his innings and he plays it well while scoring comfortably, sometimes you just have to tip your hat to the batter. However, I’d rather that happens than a batter scoring runs as a result of your own team’s poor decision-making. By getting Duckett early on, you can massively impact the flexibility of England’s batting lineup. TLDR – Don’t bowl spin when Duckett is at the crease & only bowl leg spin when Moeen is there.

That’s just one example from recent matches and the possible impact it can have on a game. Many Pakistani fans will tell you there’s plenty more where that came from. Indeed, it’s backed up by the stats as well:

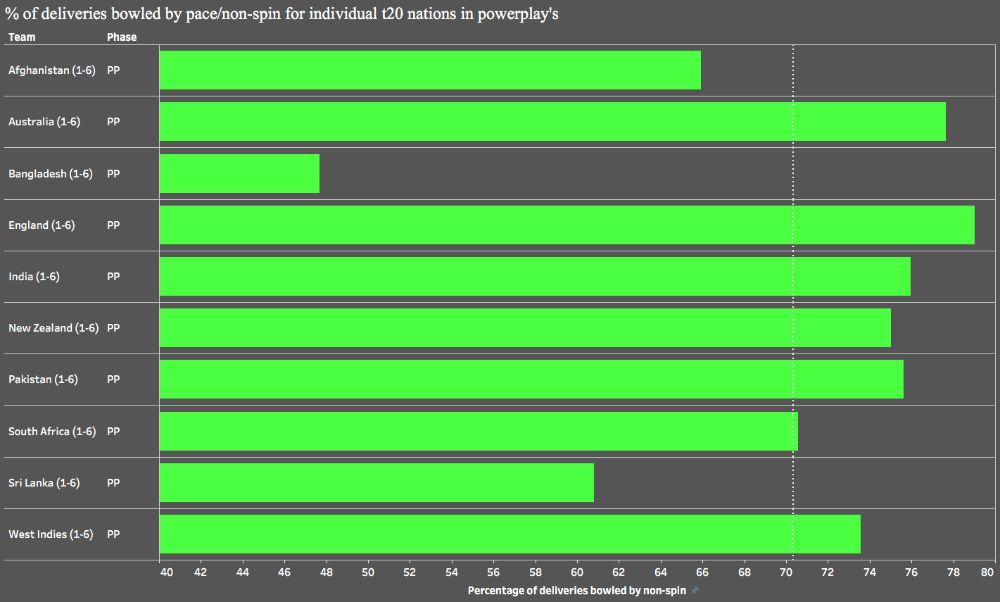

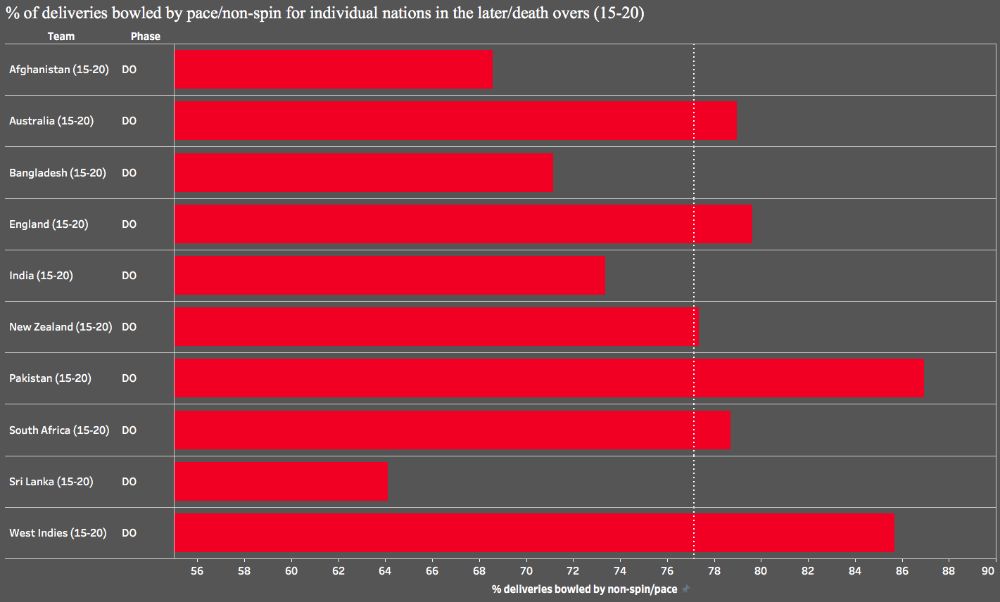

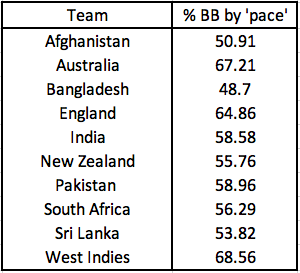

If we assume that powerplays are generally to be bowled by pacers, the 7-14 over phase by spinners, and pacers again for the later/death overs, well, Pakistan follow this template to the extreme. I guess the average for the top 10 nations indicates the amount of pace, spin & pace again that we’d expect to be bowled in those phases. As you can see from the table above, Pakistan are generally following the template of traditional thinking (Pace, Spin, Pace) by bowling more pace than you’d expect in the powerplay & at the death while bowling far more spin than average in that middle overs period. Knowing this is all well and good, but how do they compare to other teams in this regard?

Note – Lines indicate the average % of non-spin/pace bowled in each phase.

Just from looking at this graph, we can see that Pakistan have the lowest % of pace bowled in the 7-14 over phase. Therefore, they bowl the most spin and then the highest % of pace bowled in the 15-20 over phase. Again, this indicates that they perhaps have a pre-planned bowling strategy that doesn’t change much during matches. Such an approach doesn’t seem desirable and will lead to them being predictable and will be more easily countered by well-constructed batting units. To get a clearer picture, we can break it down by phase:

The powerplay is the phase where they’re most likely to show some versatility, bowling slightly more pace than the average but not significantly. It’s also important to note that many teams bowl between 70-80% of their deliveries through pace bowlers in this phase, with countries like Bangladesh & Sri Lanka being the main exceptions due to playing in particularly friendly conditions for spin bowling.

No team bowls a higher percentage of deliveries with spinners through the middle overs than Pakistan, and it’s only really New Zealand that get close to them. Considering teams like Afghanistan, Bangladesh & Sri Lanka have very strong spin attacks, yet they’re bowling a lower percentage of spin through the 7-14 phase than Pakistan surely suggests Pakistan are being far too one-dimensional with the way they structure their overs in the bowling innings.

The death overs are, once again, another part of the bowling innings where Pakistan seem to be far less versatile than other teams, bowling a higher percentage of deliveries through pace bowlers than any other team in this phase. West Indies are the only team close to Pakistan in this phase of the game, and they bowl a far higher percentage of pace overall:

Considering this, we wouldn’t expect Pakistan to be so far ahead of the likes of England, India & South Africa. Pace bowling is definitely one of the major strengths throughout Pakistan cricket, so I guess it makes sense that they want to prioritize bowling these players in crucial phases. However, a more frequent trend in T20 cricket seems to be holding back overs of spin to counter the top class of ‘finishers,’ who are often much stronger against pace than they are against spin. Pakistan don’t seem to be adapting to this trend, and I think it’s fair to assume they aren’t maximizing their current bowling resources. The ‘rigidity’ of the bowling plans is an issue.

General strengths/weaknesses of the squad

Now that we’ve covered a couple of the major strategic weaknesses for Pakistan in T20s, it’s time to move on to the more general strengths and weaknesses of the team in terms of player quality and the resources they have available to them rather than strategic problems.

In order to do this, looking at a stats sheet that compares them to other teams could be beneficial:

Note – Stats are correct as of September 19th.

This is slightly out of date and doesn’t include the matches against England because the original plan was to publish the article before the start of that series. As is often the case, things don’t always go to plan.

Looking at the more general data, only India has had a higher win percentage than Pakistan since the start of 2021. Once again, that reminds us that while Pakistan aren’t the perfect T20 side, they’re more successful than most, no matter what time period you look at. Of the eight national sides to play at least 150 T20Is since their introduction in 2005, again, it’s only India that has a better win percentage than Pakistan:

Note – Abandoned matches/no results were removed, and ties were counted as 0.5 wins. Data from Cricinfo and is correct as of 23rd September.

India and Pakistan are the only two teams (that have played at least 150 matches) since the outset of T20Is to maintain a win percentage of above 60%. If we dive deeper and look at individual time periods, we can see that even at their worst, Pakistan has won more games than they’ve lost on average:

This wasn’t as clear as we would’ve liked, so I’ve added a table to show the win percentages for each ‘time period’ in T20Is:

They’ve basically always been an above-average/good T20 side and continue to be just that. Yet, if you looked at the general level of discourse on social media, you wouldn’t expect that.

Strengths

While data is obviously extremely important, it doesn’t always represent the full picture. Suggesting that Pakistan are around the average for a bowling side since the start of 2021 doesn’t consider what we’d perceive to be their strongest bowling unit – Shaheen, Rauf, Naseem, Shadab, Nawaz plus Iftikhar/Wasim jr as the fifth bowler – has never played a game together and also that the oldest of those bowlers is 28. There’s room to grow, and with that quintet, as well as some of the players in reserve like Hasnain, bowling certainly looks to be their forte going forwards.

Pace-bowling

The trio of Shaheen, Naseem, and Rauf has all you’d want in a pace attack, really. All three can bowl at 140-145+ and can do so fairly regularly, while Rauf is one of the quickest bowlers in the world and is capable of reaching 155 when at his best. Pace with limited skill is sometimes worse than lower pace. Importantly, these guys also have incredible amounts of skill. All three are capable of bowling in the powerplay and at the death, with good success, and when you look around the world, that’s not something that many pace bowlers can do.

This data also doesn’t fully highlight the improvements Haris Rauf has made as a bowler, with his numbers across all phases trending in the right direction over the last 12 months but especially during the first six overs. In 2020 & 21, Haris had a powerplay ER & SR of 9.29 & 24.79, compared to 7.43 & 20.92 in 2022 so far. Considering he tends to bowl the later overs in the powerplay, with over 70% of his deliveries coming between overs 4 & 6, those numbers are outstanding.

As far as I’m aware, all three have never played in a game together. When it happens, which should be sooner rather than later, they’re going to cause so many issues for opposition batting lineups. Because they’re so good as a trio upfront, their death bowling abilities will slide under the radar, with Rauf, in particular, excelling in this phase for Pakistan, going at just over 8 RPO, which is phenomenal. Shaheen also has excellent death bowling numbers, though he’s performed at a higher level domestically than at the international level in that regard.

The consistency from Babar/Rizwan

In an age where the value of taking early wickets with the ball is common knowledge, and hence powerplay bowlers are so highly valued, why do we sometimes undervalue stability at the top of the order with the bat? Not all of what they do is perfect, but the consistency at which they see Pakistan through to the 6-8 over mark helps the side a lot. Rizwan, in particular, has been phenomenal in this regard, averaging over 100 in powerplays for Pakistan since the start of 2021. Of the players that have faced at least 200 deliveries in this phase in the same time period, no other player averages more than 60. You’d be naive to think that the stability they offer doesn’t benefit the team.

Lower-order pace-hitting

What Pakistan lacks in ability against spin and fast-scoring from ball one, they somewhat make up for by having good pace hitters lower down the order. Asif Ali is, of course, the most established player for this role, while Mohammad Nawaz has also shown vast improvements in this area of his game. Iftikhar has also dominated pace-bowling in domestic cricket (NT20 Cup) but has struggled to regularly convert that to PSL or international level. You get the sense that he’s a better player than he’s shown at the highest level thus far, though he’s also probably not ideally suited to the role required of him.

A fun quirk of the Pakistan side is that the tail is beginning to wag quite regularly when required; the most recent example of that would be Naseem Shah striking two sixes in the final over to win them the game against Afghanistan in the Asia Cup. You get the sense that won’t be the only time something like that happens, though Pakistan won’t want it to be required too often. If needed, the Pakistani tail can wag, and all of their bowlers have showcased striking ability in the last 6-12 months, which has culminated in their 9-11 hitting 102 runs from 59 deliveries in 2022 so far.

Spin options

If we assume Iftikhar is in the playing XI, this gives Pakistan three spin options, all offering a different variety. They’ve got a great pace attack, but if conditions/opposition strengths dictate they have to alter slightly from those plans, they have the resources to adapt. Shadab’s performance for Pakistan in the last 18-24 months have been second to none, taking 28 wickets @18, with an economy of 6.5 RPO.

Nawaz has taken over the mantle left by Imad, and the biggest compliment that you could give him is that it doesn’t feel like Pakistan have missed Imad, who was a reliable performer for Pakistan over many years. Perhaps what helps Nawaz most is that his record against LHBs is respectable, going at 8.15 RPO against them since 2019, over a sample size of more than 400 deliveries. In an era where matchups are more highlighted than ever before, that’s certainly a decent effort. Iftikhar is more of a part-time bowling option but is still a handy option to have for matchups, and his bowling has probably been underutilized by Pakistan.

Pace bowling depth

Even with one of the best white-ball bowlers in the world (Shaheen), you don’t feel like the bowling attack becomes significantly weaker, such is the depth of pace bowling quality in the country. An improved version of Haris Rauf has emerged over the last year, while Naseem & Hasnain are coming into their own, and the likes of Dahani & Wasim jr are able backups. Players such as Faheem Ashraf, Hasan Ali & Mohammad Amir seem to be out of the picture, while Zaman Khan, who was one of the standout players in the PSL season, hasn’t even had a sniff at the international level yet.

Weaknesses

Batting against spin

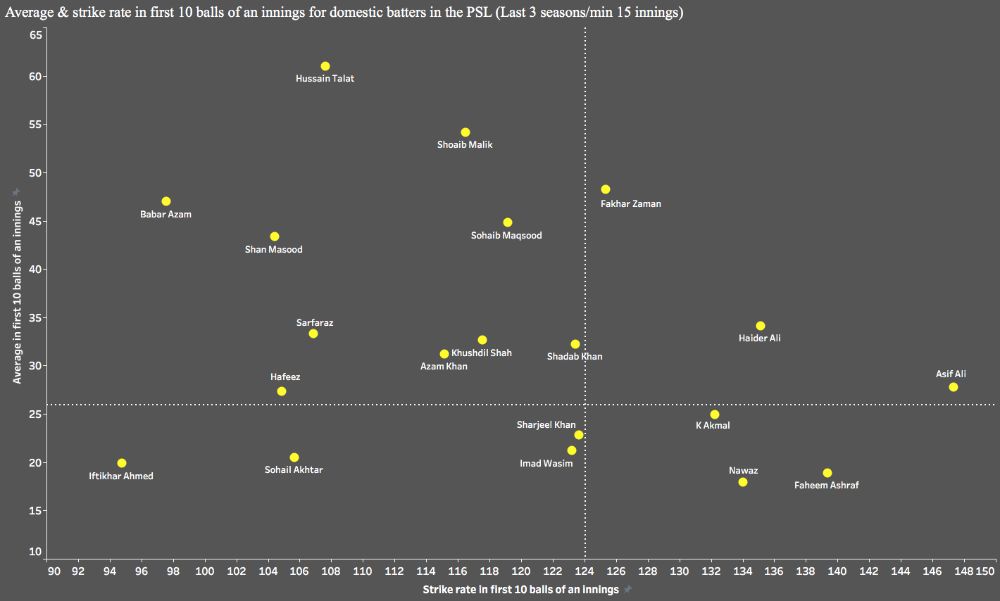

Of the seven players that have faced at least 50 deliveries against spin for Pakistan since the start of 2021, Rizwan is the fastest scorer (SR 122), and he also has the highest average (59). Only two other players have averaged more than 30 (Babar & Iftikhar), while Babar is the only other player to strike at more than 110 (his SR against spin has been 119). If we look at the numbers in the PSL, many of the better players of spin-bowling haven’t been picked.

I’m not saying Pakistan were wrong to avoid picking most of these players; you can’t keep playing a 40-year-old player forever. However, I think it highlights the importance of Haider Ali/Shadab Khan and how crucial it is that they get a consistent chance in the middle order. Of the players that didn’t meet the sample size requirement but are in the Pakistan squad, Khusdhil & Nawaz both have underwhelming numbers against spin, while Asif Ali can score quickly but is dismissed fairly regularly. Despite being secure players of spin, Babar & Rizwan also struggle to consistently accelerate against it. This is less of an issue against the top-quality wrist spinners. However, when they struggle to take down orthodox spinners/secondary bowling options, it becomes more of an issue.

Skill set shortages

One of the major issues more generally with Pakistan cricket is the skill set shortages in specific areas, which we’ll go on to explain individually here.

Slow starters

It’s a fairly common problem globally. However, it’s probably more of an issue in Pakistan than in most other countries. They just don’t have many players capable of starting their innings quickly.

The same graph with Rizwan removed for easier viewing:

As you can see from the graph, in terms of ‘actual batters’ that can start quickly, it’s Asif Ali, a big gap, Haider Ali, 40-year-old Kamran Akmal, and then there’s not much else. You have Nawaz and Faheem Ashraf, though they’ve tended to be utilized as pinch hitters or lower-order players.

Despite better pitches, a more modern approach, and the development of pace-hitting techniques, which have all led to increasing run rates in the PSL (table above), there’s still a general level of conservatism when it comes to individual players building an innings, with only a few exceptions to the rule.

Wrist spin backup

Pakistan went through a worrying phase in 2020-21, where Shadab’s bowling performances fell off a cliff due to form and injuries. They were forced to confront the fact that they had no actual backup for him and would often play him while he was not fully fit. However, the emergence of Usman Qadir went some way in allaying those concerns, with him at times looking like a better option than Shadab. But ultimately, Shadab eventually recovered and firmly established himself as the first-choice leg spinner and all-rounder, while as Qadir played more games, people began to notice the three bad balls he would bowl in an over rather than the one good one. As of now, he remains Pakistan’s wrist spin backup, but with Zahid Mahmood and now Abrar Ahmed nipping at his heels.

Zahid seems to be confined to one-dayers because of his better control, with the management reasoning that Qadir’s googly makes him a better T20 option. Unfortunately, both do not get regular PSL games to judge and compare them, but Zahid has been the best spinner in the last three seasons of the National T20 with 46 wickets @ 20.2/7.4. Abrar and Faisal Akram are different from normal leg spinners. Abrar is more Theekshena-like, while Faisal bowls left-arm unorthodox. However, both of them currently bowl too slowly to survive in higher-level T20 leagues and international cricket.

Minimal LH batting options

Pakistan’s domestic cricket is littered with SLAs, primarily because most of the batsmen are right-handed. There are quite a few left-handed batsmen, but 90% of them are openers, probably inspired by Pakistan’s only contemporary great left-handed batsman – Saeed Anwar. There are next to no left-handed middle-order batsmen, which is why when the likes of Haris Sohail or Khushdil Shah come around, they manage to rack up decent numbers in List A cricket because 10-15 overs are bowled by SLAs, which they are relatively comfortable against as compared to their right-handed counterparts.

Sindh, or actually Karachi, produces quite a few left-handed batsmen – the likes of Saud Shakeel, Saad Ali, and Saad Khan come to mind, but all of them do not have much of a future in T20 cricket because of their lack of power. Saim Ayub seemed to be another one off that production line, but he seems to have developed his power game. He may be the start of a revolution in which young Pakistani batsmen go from worrying about that high front elbow to testing their limits of how far they can make the ball travel.

The importance of Babar and Rizwan

It’s the age-old debate when it comes to Pakistan in T20 cricket – the respective roles of Babar/Rizwan, their approach, and whether it is beneficial or detrimental to the team’s ability to win games. As stated above, Pakistan has generally been one of the most successful T20 teams since the introduction of the format, and that’s been no different in the last 2-3 years. So to even suggest that the negatives of Babar/Rizwan have outweighed the positives would be extremely arrogant, regardless of what you think of their approach, and I’m not sure many would say that. However, I do think they’re often an easy target and take more of the blame than they probably should.

While my thoughts on this subject are quite strong, we also have to acknowledge that their partnership does have flaws, especially when batting first, as shown when we looked at the 10-over scores. The approach when batting first is often too one-dimensional, though I think that goes for the entire team, including coaching/backroom staff with the decisions they make, rather than Babar & Rizwan specifically. In any case, for all the criticism of their approach while batting first, are they working on it? In the series vs. England, while batting first, their two 10-over scores have been 82 & 87. Both scores are higher than 16 of the 17 previous 10-over totals in the first innings since the start of 2021. We’ll need more than two games to judge, but even if they’re being slightly more proactive, this can be seen as a positive.

More generally, Babar & Rizwan have been superb assets for Pakistan in T20s and the style of team that Pakistan are, and I think those are the crucial points that are often lost in translation. Would these two be great in every T20 team they played in? Definitely not; they might even have a negative impact in some, but for this team, they’re a great fit.

With the technically secure and consistent starts that these two offer them, combined with an above-average bowling attack, it’s almost the perfect mix and takes a lot of the burden off an often unconvincing middle order. Thus, I have no issue if Babar/Rizwan decide to take a more passive approach at times, even during the middle overs, if it involves taking fewer risks against the opposition’s best spinners. Overall, I think it would benefit the team in the majority of cases. They do a great job of soaking up pressure from the opposition’s best bowlers; if opposition attacks decide to change their plans and start back-loading their best bowlers, then the onus will be on Babar/Rizwan to react accordingly and take more risks when needed.

To me, it always seems a bit perplexing when people come up with reasons to defend the Pakistan middle order. To put it simply, they’ve been incredibly average:

Note – Data correct as of 23rd September

With the exception of Asif Ali & Shadab on occasions, the likes of Fakhar, Khusdhil, Iftikhar, Haider & Hafeez (before he retired) have all been poor over the last 18 months or so. Considering the platforms that have been set, it’s fairly inexcusable for the middle order to consistently perform as badly as they have done, in my opinion. They have the lowest average of any of the top 10 nations and a middling strike rate to go with it. As I said, considering the platforms that are regularly set for them, there’s not really any valid reason for them to be performing this badly. This suggests a lot of it is down to selecting the wrong players or using the correct players in the wrong roles.

In the long-term, there might be an option to split Babar & Rizwan in order for the team to reap the full benefits that both have to offer, with Rizwan playing the more attacking role in the powerplay, paired with a dynamic opener, while Babar comes in at 3, showcasing his security against spin and ability to accelerate against pace later on in the innings. For now, with a World Cup on the horizon, that doesn’t seem possible, and in any case, all of the ‘dynamic’ opening options are too raw and need time to grow. Thrusting them in on the main stage at this point probably wouldn’t be beneficial to the team or individual.

For now, Pakistan fans will have to settle for what they’ve got, and what they’ve got is incredible consistency that masks an underperforming middle order.

Long-term solutions to the structure of the batting order

PSL teams usually pick bowlers as their emerging players, mostly because it is easier to find young fast bowlers than young T20 batsmen. Those young fast bowlers are quicker to adapt to the demands of T20 cricket and often are able to fit into the defined roles the team may have for them – usually as the first change and 3rd death bowling option. However, in 2020, two PSL teams departed from the norm; Peshawar Zalmi and Quetta Gladiators, for nearly the entire season, played two batsmen as their emerging category players.

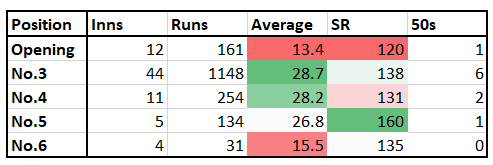

One of them would win his team two of the four matches they won that season, and the other would finish the group stages with 239 runs @ 30 with an SR of 158. For a team that does not have many options for T20 middle-order batsmen and was having to make do with 40-year-olds, this was like man-o-salva sent from heaven, but just like the Bani Israel, Pakistan was not grateful.

Haider would be fast-tracked into the XI; he would perform admirably on debut, and then for reasons outside his control, he would be thrust up the order to open the innings. Now Haider has a decent T20 record in most positions but not opening. He has shown an inability to survive the new ball in the first few overs, and Pakistan decided that they were going to open with him. That worked out about as well as anybody would have thought.

After that idea went swimmingly, Pakistan now decided a 3-game sample size was enough to try Haider in a position where the best death hitter in Pakistan had middling numbers in. And after barely giving him a fair try either, he was ostracised. All the while, voices circled him telling him how he should play and what he was doing wrong when in fact he was the one being wronged. Ultimately, he has been hounded into changing his game; he no longer attacks spinners as he once did, and he no longer starts fast, instead looking to “build an innings,” the exact opposite of what Pakistan needs after their openers. The irony of Haider 2020 being exactly what Pakistan needs right now in their XI, a fast-starting batsman who hits spin, can not be lost on many.

Meanwhile, we take a look at Azam, who did not arrive with as big of a bang as Haider but seems to be currently in a better position of understanding his game. So you have one batsman who was brought into the national setup from the word go and another who has played a handful of games for the national team. It isn’t exactly the biggest vote of confidence for Pakistan’s team management that a player outside their setup has managed to improve himself while the other has actively regressed.

In the end, Haider and Azam will always be around Pakistan’s national team because not many people can do what they do. Every time Haider goes back to domestic cricket, he proves just that. It is time Pakistan accepts them and their way of playing sooner rather than later.

Preferred XIs

I have a fairly settled view of what I think the best Pakistan XI would be for the T20 WC. While the XI is settled in my mind, the batting order should be anything but, and a certain level of fluidity is essential to give the team the best chances of success.

My XI:

I’m less convinced about the overall batting package that Iftikhar can bring to the side, and I do think Khushdil is slightly more suited to the role they’re likely to play. However, we can’t overlook the benefits that Iftikhar’s bowling can bring to the side, with his off-spin, giving them a sixth bowling option and a third spin option. Pakistan are a side that’s almost always had three spin options as a part of the XI, and it’s been a big reason for their success. Using Iftikhar as a sixth bowler, who has a respectable T20 economy rate of under 7.5 RPO, can be a useful tool for them.

I can’t emphasize the importance of flexibility with this batting lineup enough; if it isn’t fluid, it’ll fail. We’ve already seen Pakistan completely misuse Shan Masood twice in his first three T20I innings, which is not only unfair to the player but detrimental to the team.

In my opinion, the ideal top 3, for now, is Babar, Rizwan, and Shan Masood. However, there are rules that should be used as a guide to determine the rest of the batting order:

- If the openers bat out the powerplay, Haider should come in at 3 if the first wicket falls after the 7/8th over. Haider takes preference over any other batter until the 13/14th over. By this point, Iftikhar and Asif Ali take priority.

- Shadab comes in next, provided it’s before the 12/13th over. If those two fall in quick succession, then there’s an option to bring on Shan Masood again, as long as it’s before the 12/13th over.

- Iftikhar either bats after or ahead of Shadab, depending on the entry point. If the wicket that would bring Shadab to the crease falls after the 13th over, and the majority of spin is done, send Iftikhar in.

- Any later than the 13/14th over, then Asif Ali becomes the priority, as the best six-hitter in Pakistan and the only player that’s continually proven he can start from ball one. He comes in whenever a wicket is lost after the 14th over, irrespective of whether that results in him batting at 3 or 7.

- If top-order wickets fall rapidly and the top order, Shan, and Haider are all gone fairly early, that’s when I’d promote Nawaz to bat with Shadab and hopefully rebuild the innings for Iftikhar & Asif Ali to launch later on. Otherwise, I’d stick with Nawaz lower down at 7-8, providing depth, and I think the majority of the improvements with his batting have come as a pace hitter.

Above is just a more visual representation of how I feel the Pakistan batting lineup should change based on the situation of the game, with flexibility being even more crucial when batting first. It might seem strange to be picking Shan Masood, and many will disagree with it if he’s going to bat as low as 7-8 at times. However, the hope is that having that little bit of added ‘security’ in the XI will give Babar/Rizwan the encouragement they need to play with slightly more freedom. In any case, Fakhar has been below average for 3-4 years. At some point, you have to give opportunities to players that are waiting in line, and hence I find it difficult to disagree with the decision. After all, Masood has perhaps shown more willingness to attack spin matchups and crucially do so early in his innings and be successful with it, which is ultimately what Pakistan needs the most.

With that said, if Pakistan are going to continue with a more rigid approach, then Fakhar is undoubtedly a better option than Shan, with a much higher ceiling when it comes to accelerating in the last 5-6 overs.

Summary

Pakistan might not be favorites for the upcoming T20 World Cup, or maybe even the one after, but why not dream big? After all, Pakistan has something that not many nations have – an established group of core players that are on the right side of 30 that seem to understand what it means to represent Pakistan and love playing for their nation. They’re not only great players but impressive leaders that have helped spread an infectious team spirit throughout the group. Make no mistake; these players are ready to go to war for each other every time they cross that boundary rope.

They aren’t perfect, and there will be bumps in the road, but there’s undoubted quality in the squad and a growing belief that they can beat any team, in any conditions. The more traditional and rigid approach of the top order might not satisfy the cravings of a modern T20 fan, though will they care if it brings them success? Yet that approach is in stark contrast to their exuberant & powerful lower order and their blitzing fast bowlers. With Pakistan, you get a bit of everything, and that’s what makes them so interesting.

As their promising youngsters from a few years back are developing into world stars, they still slide under the radar. That might suit them; Pakistan will be happy to remain underdogs, feeling like they’ve got something to prove every time they stop onto the field.

At the end of the day, Pakistan will remain a good T20 side for years to come. Their ability to churn out high-impact pace bowlers can’t be matched by any other country and will ensure stability in the long-term, irrespective of their results in the immediate future. My thoughts on the current Pakistan approach are clear; it’s the best strategy for them to win games currently. Is there room for improvement? Sure, but there always is. Until certain players are regulars in the XI, the batting strategy might have to remain more cautious than many would like.

However, it’s easy for me to say that as a neutral who doesn’t support Pakistan directly, a certain approach may seem a more obvious route to winning. While the many die-hard Pakistan fans will share that same goal, ultimately, cricket is more than just a game played on the field. It’s entertainment, an escape route from the realities of life & something that makes fans all over the nation smile. So, who can blame them for wanting a more exhilarating approach at times? It’s a balance that Pakistan have struggled to master thus far, and who knows if it’ll change in the future, though it’ll likely be forgotten if Pakistan brings home a T20 World Cup in the process.

They aren’t favorites by any means, but with the correct XI and a few strategic tweaks, you’d be brave to completely rule them out.

Leave a Reply