Cricket’s Spin Doctors – How Spin-Bowling Works

Flight, drift, break, and bounce – What exactly goes into making the ball spin?

Pakistan is undeniably a land rich in pace resources. Over the years, we have carved our name in history through them, and every commentator lauds the seemingly never-ending stream of young, bright-eyed fast-bowlers making their way through the ranks whenever a new one debuts. And why shouldn’t they? The thought of Pakistani fast-bowling evokes images of run-ups all the longer to fill panic-stricken batsmen with nervous anticipation, silver chains whirling around necks, sweat-slicked hair bouncing at the point of release – it’s a 4-letter word beginning with S that I can’t say, but everyone thinks.

Much less glamorous and flamboyant, however, is fast bowling’s over-shadowed, under-appreciated young brother, spin-bowling – less exciting, less adrenaline-inducing, just less. Down to the physical toll it takes, where young fast-bowlers flirt with danger with every delivery, contorting their bodies and muscles into configurations barely the right side of sustainable – a spinner’s physically economical action, in contrast, even produces vastly less sweat.

Historically, it has been derided for its primary role in containing runs rather than for the more glamorous purpose of taking wickets (despite Muralidaran’s comfortable position atop the wicket-taking charts). However, as the game has evolved over the decades, it too has undergone renaissances and public perception shifts spearheaded by the likes of Abdul Qadir and Shane Warne. None of these have served to demystify the science of spin, however. Despite its reputation of being less, the multiple variations and possible deliveries certainly serve to make it slightly more complex to understand than pace and swing.

This journey is slightly aided by the layman’s obvious understanding of what it means to spin. Scientifically defined as the circular motion of a body around its axis, cricket’s inclination to be generally fuss-free and obvious with its labels means someone with absolutely no knowledge of the sport will be able to understand that the defining characteristic of spin bowling is the rotation of the ball as it moves through the air.

The most casual observer of cricket even ought to be able to note the key differences between pace and spin – the run-up, or lack thereof; the proximity of the keeper to the stumps; the markedly more rapid rotation of the ball before its bounce when bowled by a spinner. Two basic characteristics are therefore gleaned – that the ball is delivered with low speeds, often between 40 and 50 mph, and that the bowler has to impart spin to the ball.

The aerodynamical repercussions of this latter statement are interesting and require, as usual, some physical groundwork to be laid. There are three forces that oppose or interfere with the motion of the ball – gravity and a resistant drag force being obvious.

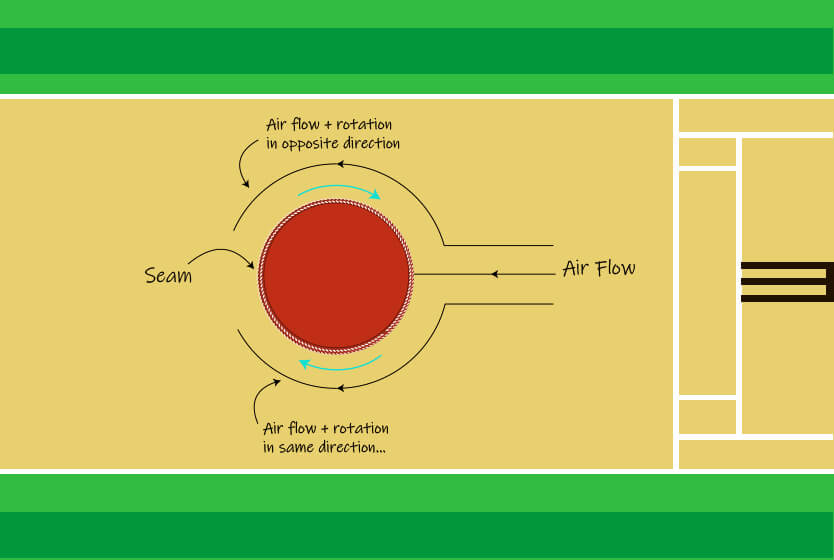

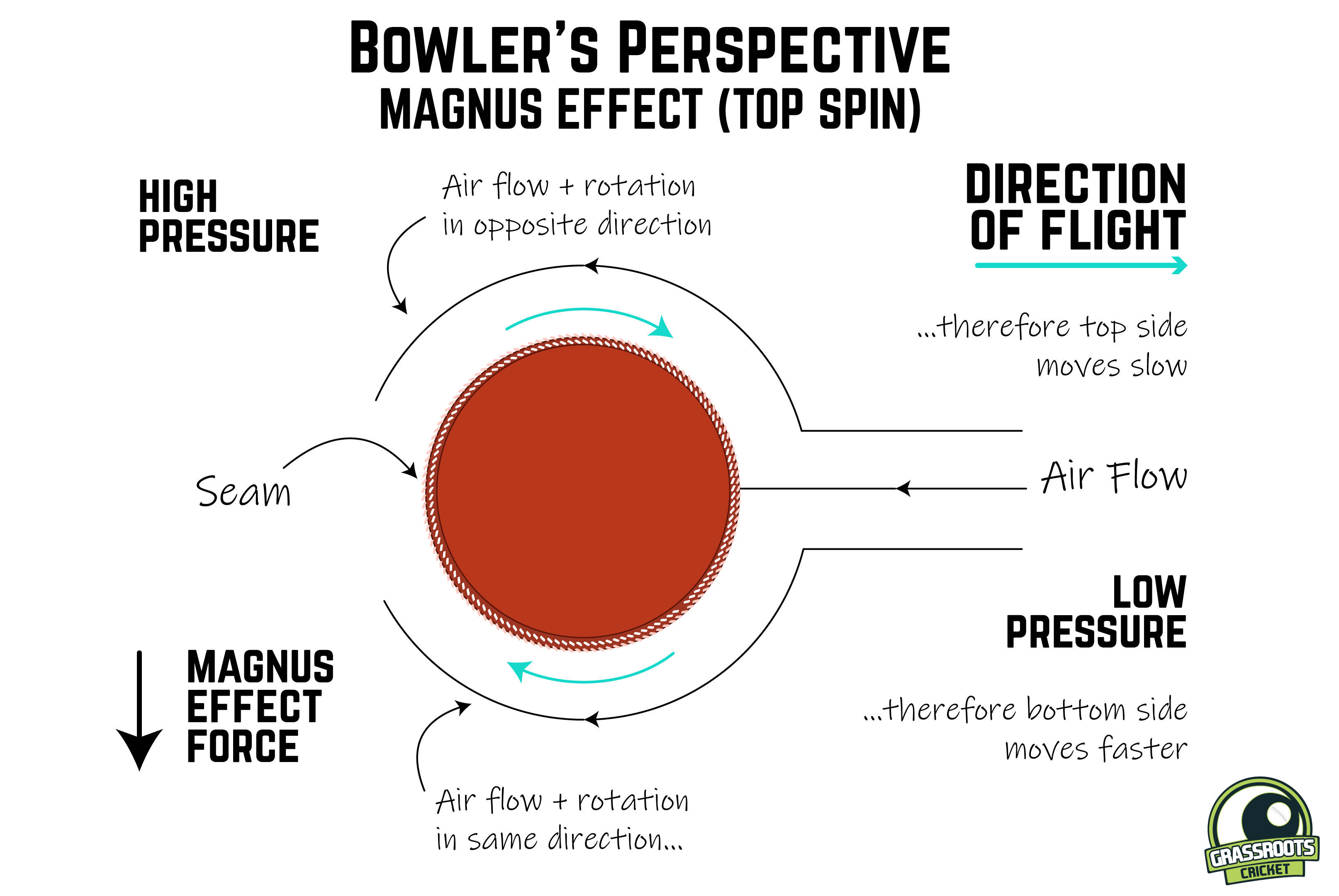

The third force is called lift, or the Magnus force, and acts on rotating bodies. This spinning motion drags air around with it; the side of the ball where the relative motion is in the same direction as the airflow is moving faster than the side where the motion is opposite. This causes a pressure difference, as per Bernoulli’s Principle, which states that an increase in the speed of a fluid results in a pressure decrease; this gradient across the ball leads to a net force and hence, lift.

Physicists are not quite so partial to clear and simple labels – the force labeled lift does not necessarily lift the ball and varies in direction, depending on that of the ball’s spin. The different directions of the ball’s resultant movement, whether sideways or vertically, are fortunately given intuitively understood labels by the cricketing community.

The direction and amount of drift is easily manipulated via the angular momentum vector – in layman’s terms, the position of the axis the ball rotates around, or the direction of the spin, to simplify it even further. Spinning the ball in opposite directions will reverse the side of the ball where the relative motion is the same as the airflow, here taken to be coming towards the bowler.

Topspin is when the ball is rotating in the same direction as its movement – the Magnus force causes it to experience a downwards force and bounce faster but also closer to the bowler, referred to in cricket as dip. The opposite, backspin, has the ball rotating in the opposite direction to its motion; hence, there is lift, an upwards force, and it bounces slower and closer to the batsman. In both of these situations, the axis of rotation is horizontal – if this is shifted to being vertical, sidespin is achieved. This does not affect the ball’s vertical motion (how close the ball drops to the batsman). Rather, it introduces sideways movement of the ball – drift, while the ball is in flight and a break after bouncing.

Many labels are bandied about in reference to spinners, but people don’t often know the exact difference in technique that sets them apart. There may be a general idea that it is to do with the direction of the ball’s lateral movement – towards the offside or legside, or the bowling mechanism, both often conveyed in the name.

| Wrist spinner | Finger spinner | |

| Right-handed | Leg spinner | Off spinner |

| Left-handed | Left-arm unorthodox | Left-arm orthodox |

Spin falls under the two major brackets of wrist spin and finger spin, which label the biomechanical action used to impart spin to the ball. In finger spin, the fingers are rolled over the ball upon delivery, and in wrist spin, an additional wrist action is included to help induce revolutions. A right-arm finger spinner is called an off spinner, whose delivery moves away from the offside, while a left-armer bowls left-arm orthodox spin.

A right-arm wrist spinner is a leg spinner whose delivery moves away from the legside, and a left-armer bowls left-arm unorthodox spin. The compactness of the notation for leggies and off spinners is simply to do with the frequency of their occurrence as right-armers. As for what makes a delivery orthodox or otherwise, deep dives into the Wisden and Google Scholar archives have been unable to demystify.

The list of different deliveries by spinners far outnumber the variations available to a pacer, many of which have little scientific research done on them. Several key deliveries make up the bulk of each spinner’s arsenal – all used to various effect.

The stock delivery is the bowler’s main delivery, often neither gifting runs nor achieving a wicket – low risk and low reward – and often used to coax the batsman into lowering their guard before pulling out a variation. For both off spinners and leg spinners, the stock delivery is a break – upon bouncing, it breaks away, spinning towards either the batsman’s legside or offside.

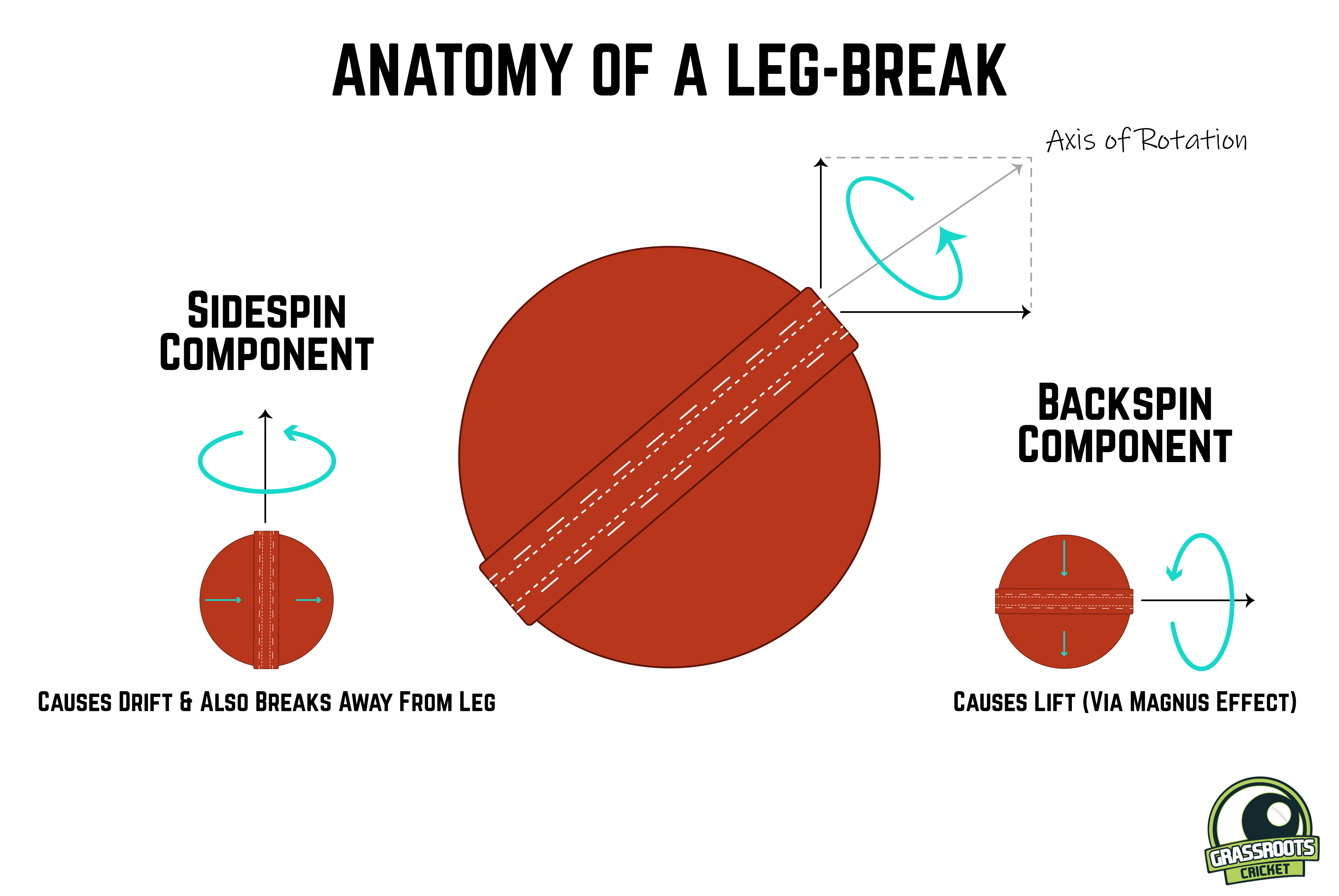

For a right-handed batsman, a leg break will break from leg to off, spinning around an axis perpendicular to the seam and anticlockwise from the bowler’s perspective, while an off break will both break and spin the opposite way. The lateral motion of the ball is due to the sidespin being imparted. However, both breaks are able to dip, a behavior that is driven by topspin. This is due to the bowler holding the seam of the ball at an angle to the direction of flight – the spin will have a horizontal and vertical component. Therefore, depending on the skill of the bowler and their ability to maintain the position, the ball can befuddle batsmen even further.

| Leg spinner | Off spinner | |

| Stock delivery | Leg break Anticlockwise spin | Off break Clockwise spin |

| Opposite delivery | Googly Clockwise spin | Doosra Anticlockwise spin |

Understanding how the components of spin work makes it easy to elevate the stock delivery to get variations. Imparting spin to the ball the opposite way should cause it to break in the opposite direction – for a leg spinner, clockwise spin will make it move from off to leg, and for an off spinner, anticlockwise spin should cause it to move from leg to off.

And we find this is exactly what happens – the opposite of a leg break is the googly, and the opposite of the off break is the doosra, discovered and popularised by Pakistan’s very own Saqlain Mushtaq. In typical Pakistani fashion, accusations of illegal actions and chucking follow the doosra whenever it is attempted to be utilized – the tricky nature of the action makes it easy to see why. Despite being a logical progression from the stock ball, it is a relatively recent invention.

And the list of deliveries goes on, accounted for by minute variations in finger positions, extra snaps of the wrist, different release points in the arc of the arm’s swing – seemingly insignificant changes that all serve to cause the ball to move in new and different ways that mystify batsmen.

The spin bowler’s armory is constantly evolving, constrained by cricketing regulations but liberated by the potential of an interesting seam position-rotation direction-bowling action combination to do something new. The modern game has evolved beyond spinners simply containing runs to a level where they are just as much superstars as their pace counterparts.

The young boys and girls workshopping their wrist movement in the alleys of Karachi and counting out the right number of steps in their walk-up in the back gardens of Evington adorn their walls with posters of Rashid Khan and Shane Warne and dream of the day they bowl the ball of the new century.

Leave a Reply