Azam Khan and The Sports Fan’s Need to Go After a “Culprit”

There’s nothing that a (losing) sports fan likes more than a punching bag. The root of all evil. The boogeyman of the team. The sole reason for everything that goes wrong. The (gasp) nepotistic selection, only in the team because of his family/friends/acquaintances. Because for some of us, sports are not just a form of entertainment that occasionally brings us the craziest highs a human can experience and, at other times, results in depths of despair. No. It’s a way of life. It is life. And if something goes awry, the culprit™ behind that must be unearthed and forced into submission. The nature of team sports dictates that in a loss, there is always a match ka mujrim.

Occasionally, this desire for a coping mechanism, combined with preconceived notions and confirmation bias, forms a deadly combination. Such as when you have a team that consistently delivers poor outcomes combined with a culprit™ who – for obvious reasons – is an easy target. In days gone by, we fans would take out our frustrations in gatherings or among friends – or at most with chants aimed at culprit™. But not anymore. We are now emboldened to go further since we have access to said culprit™ via social media platforms. Powered by anonymity and at no risk of being held accountable, social media brings out the worst in us.

For young sportspeople, social media looks alluring. Here is a place for you to showcase what you can do and celebrate your achievements. Gain a following. Connect with us, the fans. But do we – the fans – ever wonder why these same sportspeople get curated PR agencies to do their work for them after a while and walk away from this medium? The more experience a player gets, the more likely they are to tune out of social media – and indeed encourage others to do the same. That is because of us, our coping mechanisms, and our desire to force the culprit™ into submission. Show them how terrible they are by any means necessary.

When Babar Azam speaks on a public platform and thanks his fans – and simultaneously requests them to avoid negativity and abuse, there is a reason. When Shaheen Shah Afridi explains that teams and players need to be supported most when the chips are down, there is a reason. These are unquestionably Pakistan’s two biggest cricketers and have seen it all, now backed by legions of fans. But even Pakistan’s biggest sporting stars have been the culprits™ and on the receiving end of our way of life as sports fans, our methods of coping.

And so, we come to Azam Khan – the son of Moin Khan – which clearly means to US, the fans, that he is a product of nepotism. Moreover, it’s obvious that he is overweight for an athlete, which clearly means to US, the fans, that he is no good at his job. These are our preconceived notions. All that is left is confirmation bias. See, it isn’t the case with every culprit™ that the outcome is so apparent beforehand. We don’t always have a stick to beat someone with before they even get started, let alone two.

When Azam Khan fails, confirmation bias kicks in right away. His failure is unprecedented. He must be a product of nepotism! Surely his father is the one who got him selected in the Pakistan team. But this is just the start. If he falls to a bouncer from the world’s fastest bowler, that is obviously because of his weight – and the same factor is behind him dropping an absolute dolly of a catch. And a combination of both factors is the reason for him being here in the first place – fitness standards being disregarded due to nepotism.

The only thing missing from this equation is objectivity – critical thinking and logical analysis – which may lead to a less destructive outcome.

See, if Azam Khan is really only selected because of nepotism, it would make more logical sense for that to have happened years ago, when he had no performance to back him up. Not now.

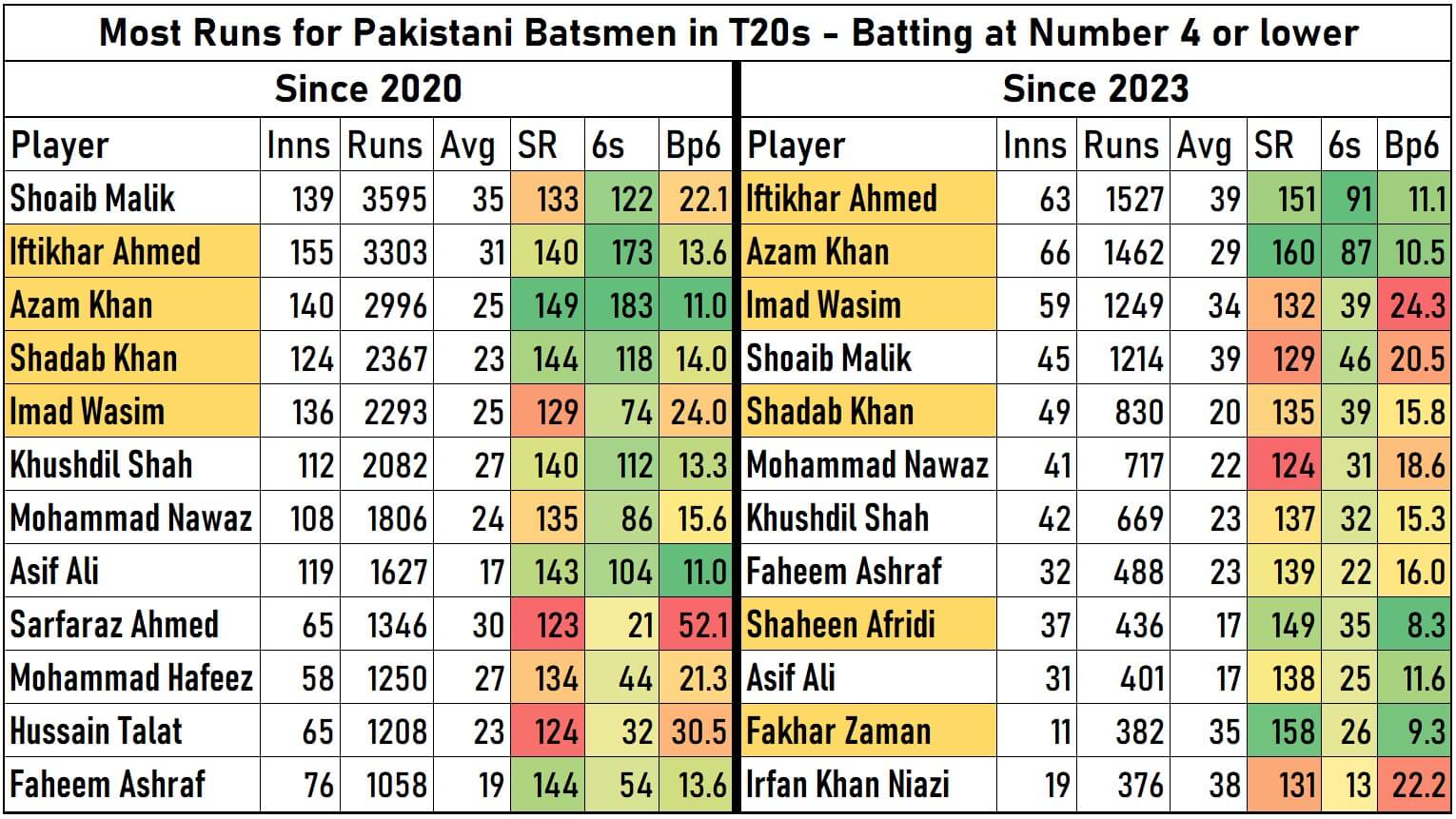

But, we will respond, that was in lowly league cricket. This is the big stage. There are plenty of other players more deserving than him. Except, logically, this doesn’t make sense because if there were other, more deserving players, they would have performances to back themselves up at any level – league cricket or not – which obviously isn’t the case. Surely selecting someone without any performance to show for it is… against merit? And we, the fans, aren’t particularly keen on most of the other options in the table above. Heck, most are former culprits™.

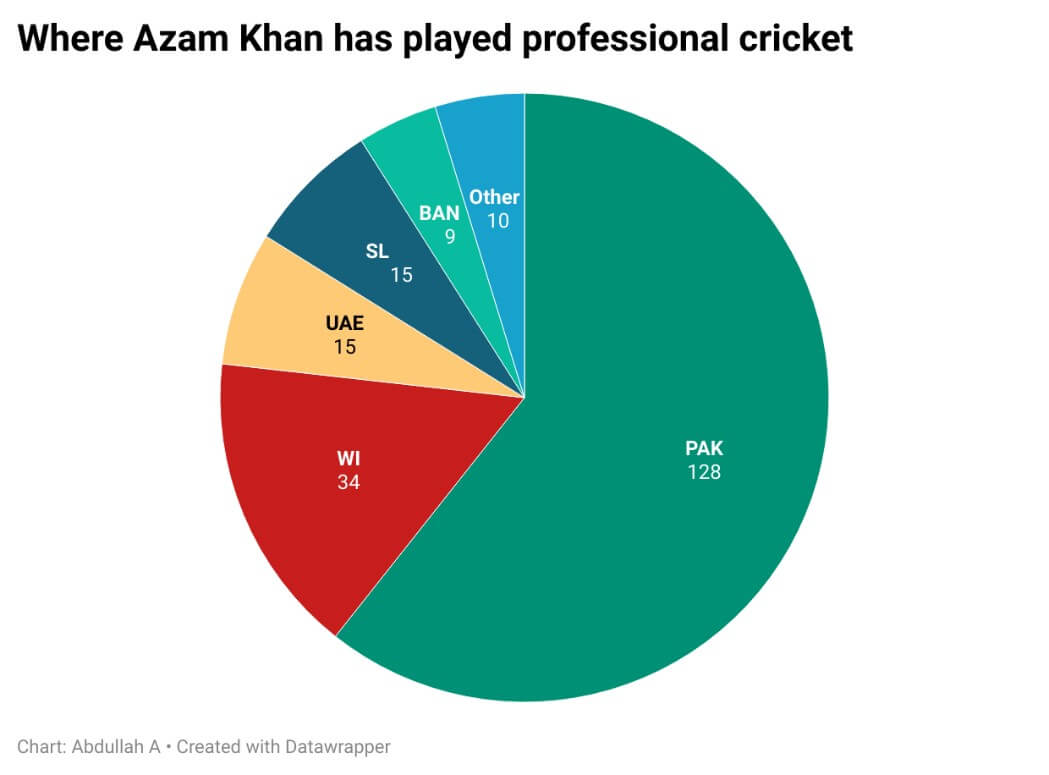

What about how he is incapable against quality bowling? At his best, Mark Wood can bowl spells averaging 150kph+ and has troubled the best batters in the world with his pace and bounce. Perhaps it’s not so outlandish that someone facing him for the first time may struggle. Azam Khan initially made his name as a strong hitter of spin who, over time, became more adept at facing pace. But, most importantly, he has played almost all of his career on Asian or Caribbean tracks, most of which don’t have the bounce you will find at venues in Australia and South Africa or even England and New Zealand – where he has played a combined 7 games.

Azam Khan wouldn’t have impressive head-to-head records against Haris Rauf, Naseem Shah, Mohammad Hasnain, and Mohammad Amir, among others, if he wasn’t competent at playing pace bowling. In fact, that was something he struggled with 3 years ago but has improved significantly since then. And substantial failure at the start of a player’s career isn’t something unprecedented – Jos Buttler and Hardik Pandya’s T20I careers being prime examples. A little closer to home, Mohammad Rizwan.

Most notably, it’s not difficult to understand why a strong hitter who favors front-foot play may struggle with hard lengths and bouncers (and no, the primary reason isn’t being overweight). Several middle-order T20 batters strive to overcome this challenge. Nicholas Pooran briefly had his T20 career derailed by bowling sides adopting just this strategy, but he has evolved as all good players do to try and mask their weaknesses. Above all, in a team game, you need players with varying strengths, and they mask each other’s faults. AB de Villiers was a once-in-a-lifetime exception, not the norm.

Dropping absolute dollies, like the one edged by Will Jacks off Haris Rauf, is not because of a keeper being under or overweight. Every single keeper, great or not, including the likes of Mohammad Rizwan and Sarfaraz Ahmed, has dropped sitters and missed easy chances, and low confidence is usually a major contributing factor.

This isn’t intended to be an in-depth breakdown or analysis of Azam Khan, although there is much more to discuss. Rather, it is an attempt to introspect and understand our own psyche. We, the fans, are massive stakeholders in sport. Indeed, there wouldn’t be any sport without watchers and supporters. But we’re also human beings with the ability to choose between dogma and confirmation biases versus objectivity and logic. Many opt for the latter and criticize within certain limits, but many of us also choose another route.

And so, when that freedom of choice results in torrents of abuse on social media or the generation of AI content to mock players, it’s just the start. The nature of social media pile-ons dictates that. Eventually, we see this lead to direct abuse under players’ social media posts, be that wishing illness/death upon Azam Khan’s family, disrespecting Shan Masood’s departed sister, or even just plain death threats aimed at players – all of which have happened in the recent past – which is pure degeneracy.

See, not every player or celebrity has their social media accounts managed entirely by a PR agency, although they probably should for their own sanity. Sometimes, they might have just had an off day, so they give in to the temptation and check their notifications and see what it’s like… and discover outbursts of vile abuse for being the culprit™. In that case, it might just be better to call it a day and maybe even remove all their social media posts, as Azam Khan did yesterday to block out the noise. That is the outcome of OUR way of life, OUR coping mechanisms. Perhaps, at this point, it’s time for some introspection.

Leave a Reply