From the Desk of a Long-Suffering Pakistan Women’s Cricket Fan

The Super Over win versus New Zealand on Monday marked the end of a largely successful away tour for Pakistan. Though the memory of the second ODI may haunt us and the fact that NZC didn’t facilitate Pakistani broadcasters still stings, the team’s success on this tour and the surge of appreciation and recognition online feels historic. There’s much to be grateful for: Fatima Sana’s all-round excellence, Aliya Riaz’s clutch performances, Bismah Maroof’s return to form, Nida Dar’s faith in her youngsters, Najiha Alvi owning the all-format wicketkeeper-batter spot…

Now, after securing our first-ever T20I series win in SENA and a hard-fought ODI win, we fly home for a few weeks of well-deserved rest. Our next international fixture isn’t until February 2024, an 8-match home series versus West Indies. So that leaves roughly 6 to 10 weeks of rest, recovery, and not much else for our cricketers. Unless, of course, we wake up one morning to find that there’s a domestic tournament beginning the next day that’ll last a few days, and it has three teams – four if we’re lucky – and one of those teams has most of our international level players and another one of those teams has no international level players and the location is a rather random ground in Karachi or Lahore where the expected score is 180 to 200 and also the innings lasts 45 overs, and the press release doesn’t mention how we can follow or watch the games, in-person or online, but if we download CricHQ, we may or may not find live scores and there may or may not be times where we keep refreshing the app, but the scorecard doesn’t change, and there’s no way to know why that’s happening.

So, in case that happens, I suppose our cricketers will have something to do in their time, at least for a few days.

But that’s yet to be seen because things in Pakistan women’s cricket are seldom planned or announced in advance. You see, there is no scheduled domestic season for Pakistan women’s cricket. There are no regions or departments – not anymore, at least – that scout and give opportunities to selected players. As a system, we have averaged one tournament a year for many years now – and “tournament” is perhaps too generous a word for what is typically a ten-day, three-team affair: a tri-series may be a more apt term. The teams in our haphazardly scheduled “tournaments” are named things like PCB Dynamites and PCB Blasters, which is fine, you know, but they falter in comparison to names like “Water and Power Development Authority” or “Karachi Whites” that you can really identify with, sort of. There are no broadcast deals with ARY ZAP. There is no entry, free or otherwise, for fans. We’re lucky even to get some games at our main stadiums, and that’s typically only when no men’s team of any level is using them.

But, of course, this year, things are different. The PCB awarded a whopping 80 contracts to domestic players! The system is developing! The pool is growing! There will eventually, at some point in time, be a tournament for our 80 domestic contracted players to actually play domestic cricket!

So, we wait.

While the BCB carries out its inaugural intra-school cricket competition and while the BCCI wraps up its sixth (!) tournament out of a total of nine across formats and levels in their 2023 domestic season, we wait for the PCB to announce something, anything of substance that will actually improve our setup and develop our players.

PCB, if you’re reading this, just announce the T20 exhibition matches that will go with PSL. We’ve long given up on the PWL (short for Pakistan Women’s League – that is what I call it, but it is not its official name because it does not actually exist yet) happening any time soon. So just announce the exhibition matches. Tell us you’re increasing the number of teams this time, that there will be more matches and better scheduling, that you’re in touch with boards all over, and that there are more talented foreign players coming to town. With that, throw in another false promise about the full league being in the works. Appease us. Please.

Actually, while I’m asking and while you’re reading, PCB, give us a proper one-day tournament, too. Six teams: double round-robin, a qualifier, two eliminators, and a final. Fix it into our domestic calendar. Free up Gaddafi Stadium, Pindi Stadium, NBCA, or Multan Stadium for the entire tournament. Set up a fancy broadcast deal with ARY, PTV, Tapmad, or all three. Open entry for fans and instruct the curators to make the pitches flatter and more suited to proper ODI cricket. Make the bowlers work for their wickets and teach the batters what it’s like to bat long and construct an innings when the pitch doesn’t spin them out of the game. Give us the proper senior one-day tournament that we should have had years ago. And then replicate it at the U19 and U16 levels, please.

I’m desperate, PCB. You have to understand that one-day cricket is far more important than you seem to think. Yes, we’re good at T20Is, and another domestic T20 tournament is always welcome. Fix that into the calendar, too, so we can set a time in the year to fawn over Eyman Fatima and Aroob Shah’s balls-per-six numbers and ooh and aah over the many up-and-coming spinners we have. Beyond the domestic system, too, our senior team in T20Is is looking good: Fatima is clicking, Aliya is Aliya-ing, we have more capable top-order batters than we can handle, and our spin attack is to die for.

But ODIs… I’ve just seen the ICC ODI rankings, and I’ve looked over our numbers in the last six years and trust me when I say I have every reason to be concerned. We need the one-day tournament, and we need it fixed into our calendar.

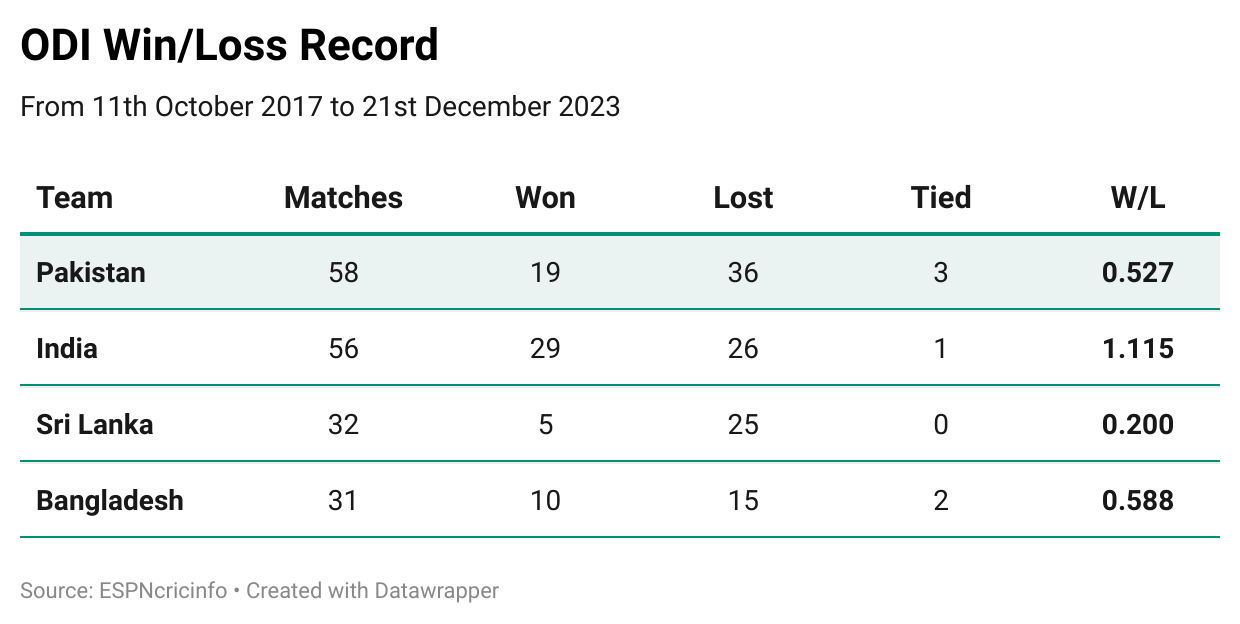

From October 11th, 2017, which marked the start of the 2017–2020 ICC Women’s Championship, to December 21st, 2023, Pakistan have played 59 ODIs and won just 19. We are currently ranked 10th in the ICC ODI rankings, below Thailand and West Indies amongst others. Now, ICC rankings may not be the best judge of cricketing ability, so consider this instead:

Notes:

- W/L = win/loss ratio

- For much of this article, I present data for Pakistan in comparison to India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. These are the countries we are most often compared to (hashtag South Asian sisterhood) and the countries we should be looking at for competition and inspiration when it comes to domestic systems and match performances home and away. This is particularly true for India and most recently, true for Bangladesh as well. We have a lot to learn from these two. Sri Lanka, too, is on the rise, albeit more slowly than the rest, and so their numbers have been included as well.

Where does Pakistan stand in comparison to other South Asian sides: India (ranked 4th), Bangladesh (ranked 7th), and Sri Lanka (8th)?

The table says we’ve played more ODIs than all of them in the last few years. And our win percentage is well behind India’s but also behind Bangladesh’s. While Bangladesh is spinning a web around South Africa in South Africa after doing the same to us at home a few weeks prior, and while India is comprehensively winning a Test versus England and having a cracking first day versus Australia as I write this, we’ve won only 3 ODIs this year (1 of which was a Super Over win) and lost a whopping 6. And out of those 6, only 2 were close losses.

We just aren’t a good ODI side right now.

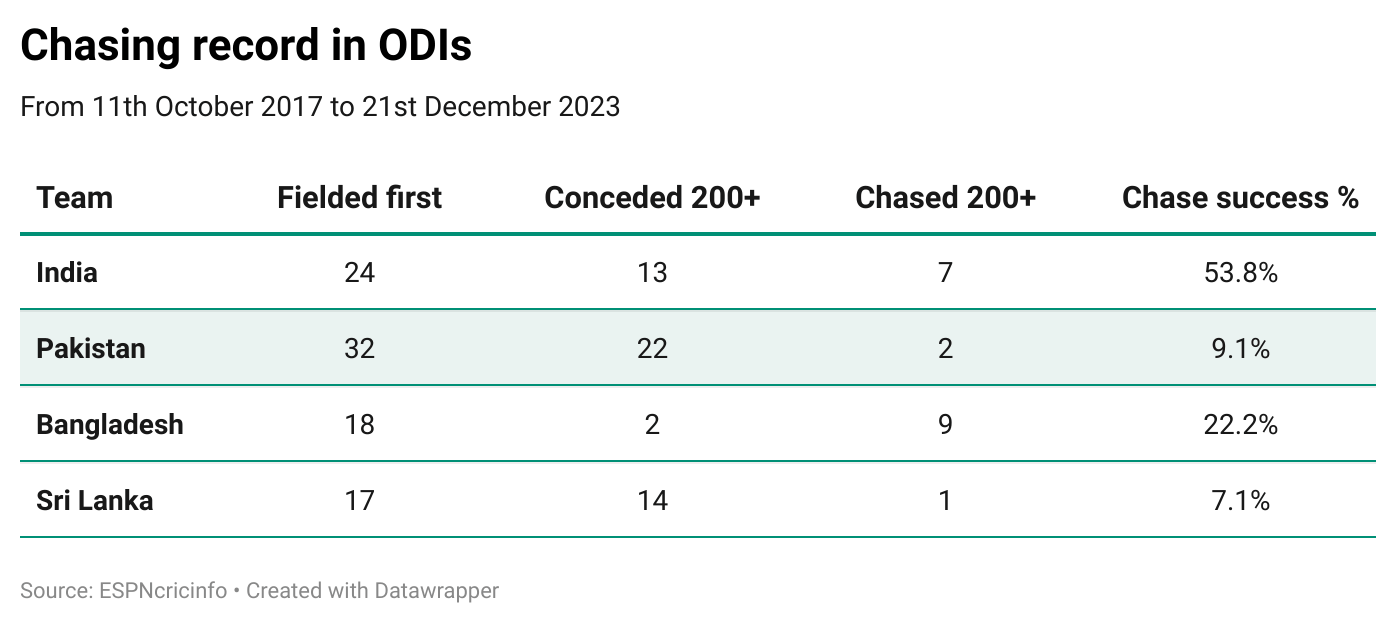

Since October 2017, we’ve only ever chased 200+ twice in 20 attempts – and never against top 5 teams. We have tied in 200+ chases twice, once versus SA (no Super Over, but yay Aliya!) and once versus NZ (Super Over won, yay Aliya!). For comparison, India has chased 200+ 7 times in 13 attempts (tied once), while Bangladesh has done it twice in just 9 attempts.

Not only does this mean that India and Bangladesh have a much higher success rate (see table), but it also means that while Pakistan have conceded 200+ 22 times in 32 innings bowling first, Bangladesh have only conceded 200+ 9 times in 18 innings, and India have done so 13 times in 24 innings.

In this time period, we’ve batted first 27 times, and we’ve scored 200+ 12 times. In those 12 times, only 4 times have we crossed 250 — and never against the top 5 teams. The ability to set a score at 4 to 5 RPO in an ODI and the consistency at which you do this is a pretty good indicator of your batting unit’s strength in ODIs. Though crossing 250 is still a bigger feat than one might expect, considering pitches and the general tempo of ODI games in women’s cricket, the fact that India’s crossed 250 11 times in 32 attempts indicates we’re lagging well behind. They have, for reference, crossed the 200 mark 24 times in comparison to our paltry 12.

Even batting for a full 50 overs, or close to it, when batting first is a fairly decent judge of how solid your unit is. It suggests that your side played a respectable number of deliveries, batted it out, and constructed a “proper” ODI innings for the bowlers to defend. This isn’t hard science, mind you; I haven’t checked the correlation between batting 45+ overs and being a good ODI side. I’m just saying if your batters are playing out a full innings, it’s likely they are playing ODIs the “right” way: that is, they built their innings, fought through the middle overs, prevented collapses for the most part, and ended on a decent total. And batting first, we’ve faced at least 45 overs 17 times out of a total of 27, which isn’t so bad – but then you see, India has done so 29 out of 32 times, and our 17 doesn’t look that good anymore.

PCB, I’ll do you a small favor. If you didn’t read all the numbers I just threw at you in the last few paragraphs, here are some tables that display that data. I’ve added the success rates for good measure. Take a look to see how we’ve fared, especially in comparison to Bangladesh and India. It’s not pretty.

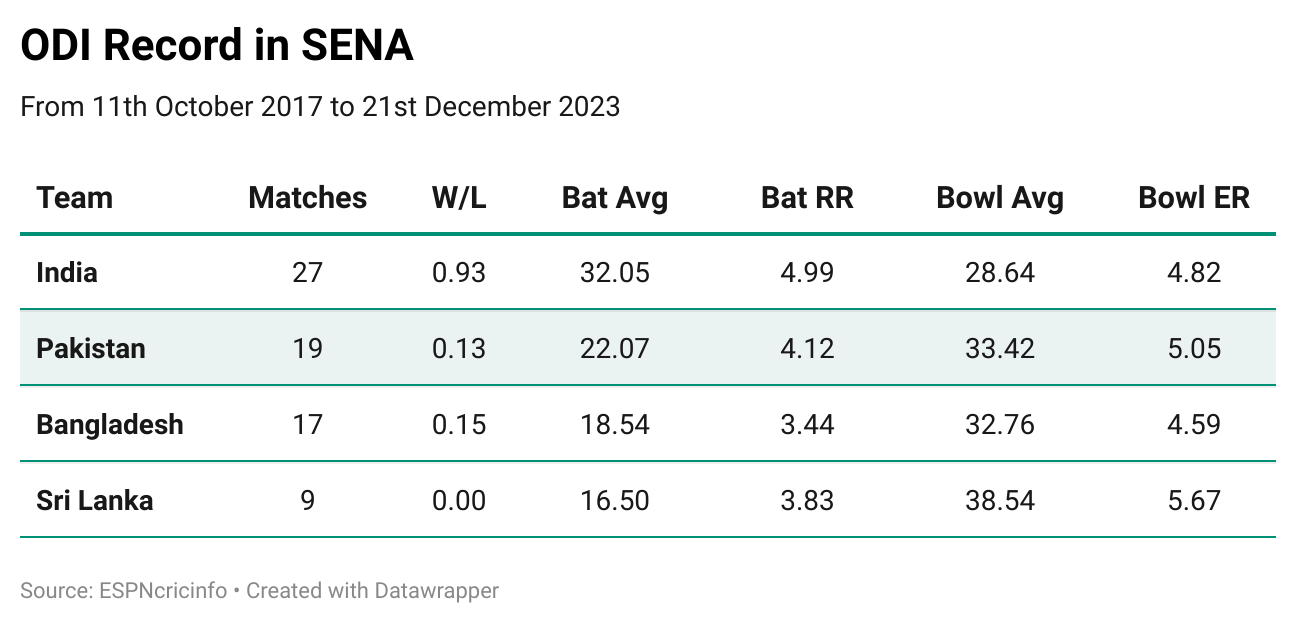

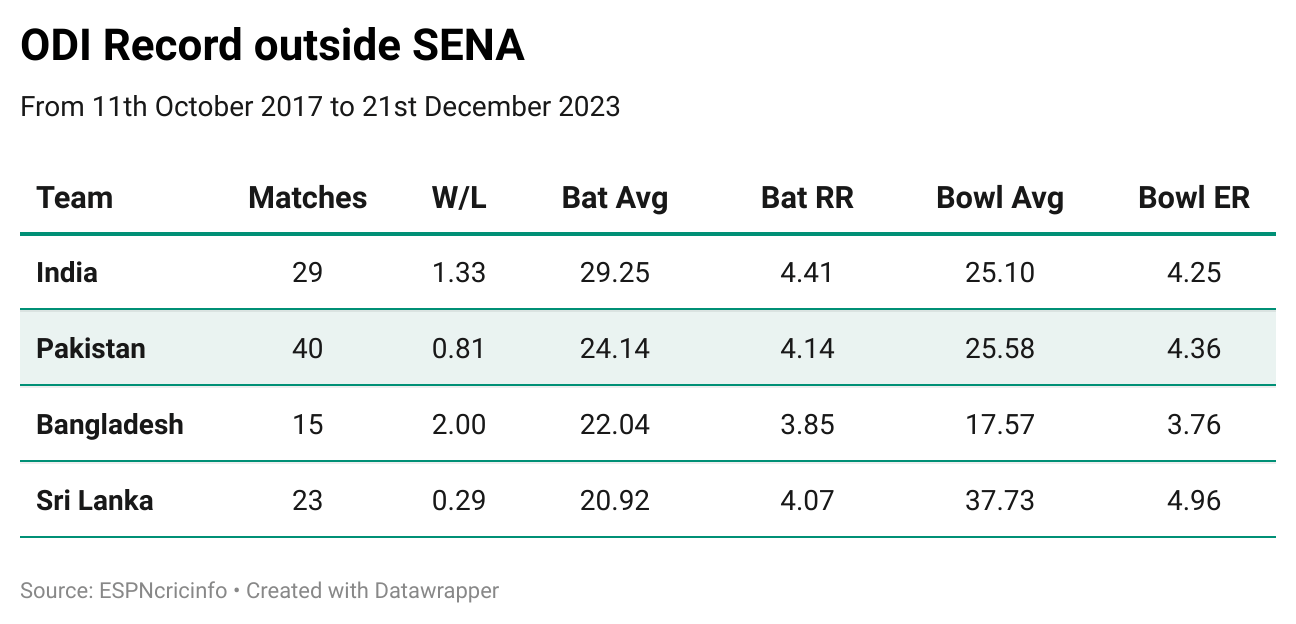

Our bowling, too, hasn’t been quite as competitive. We’ve only bowled out oppositions 18 times in ODIs since October 2017. But some better metrics, perhaps, that suggest our bowling and batting are falling short in ODIs across conditions are in the two tables below:

Notes:

- W/L = win/loss ratio

- Bat Avg = team batting average

- Bat RR = team batting run rate

- Bowl Avg = team bowling average

- Bowl ER = team bowling economy rate

- SENA = South Africa, England, New Zealand, and Australia

- Outside of SENA = everywhere else, including parts of Europe, all of Asia, the West Indies, and parts of Africa.

What do these tables tell us?

- India bat much better than the 3 other South Asian sides in SENA and also outside of it. This isn’t a surprise, really; they’re the best South Asian side by a margin. Their much superior W/L numbers (particularly in SENA) confirm this.

- India bowl better, too, in SENA, though Bangladesh are by far the most economical side, even in SENA’s typically less-spin-friendly conditions.

- Outside of SENA, Bangladesh are incredible with the ball and have an excellent W/L ratio to show for it. But the number of matches they’ve played in these 6 years is quite low, and this is a shame. India and Pakistan fans know all too well how much of a challenge it is to beat Bangladesh at home and other spin-friendly conditions and they should play more games in these conditions to show for it.

- Unlike Bangladesh, Pakistan doesn’t have much to celebrate. Their embarrassingly low W/L record in SENA is complemented by the gulf in their batting run rate (4.12) and their bowling economy rate (5.05), which indicates how quickly we score – not that quick, as you can tell – and how quickly teams score against us, which is pretty quick.

- Outside of SENA, our record gets better. We’ve had a particularly successful run in the last two years at home, losing just 3 in 9 games. Still, unlike India, whose overall batting average and run rate are better than their bowling average and run rate in and out of SENA (which is a very good thing), Pakistan’s numbers in the two tables show that even outside of SENA, we fare worse than our oppositions. That, like a win/loss record of less than 1, is enough to indicate we are not a very competitive side. In fact, we’re not even a mid-tier side in terms of competitiveness: we’re low-tier, we’re hardly competitive.

But you might ask, why aren’t we competitive? Why aren’t we scoring quicker than our opponents or getting hit for fewer runs than them? Why aren’t we taking wickets faster than we lose our own? Why aren’t we scoring 200+ or 250+ more often? Why aren’t we bowling oppositions out? Why are we lagging behind Bangladesh and India in the format that we’ve been playing for 26 years? (Fun fact: Bangladesh has been playing it for just 12 years.)

Well, PCB, I don’t want to point any fingers, but it certainly doesn’t help that there is no one-day tournament fixed into our calendar and that we don’t have a calendar at all. It also doesn’t help that one-day and T20 tournaments happen rather erratically, that the system is upheaved every few years, and that new administrations must be reminded to throw in a week-long joke of a tournament towards the women’s wing as an afterthought every other year.

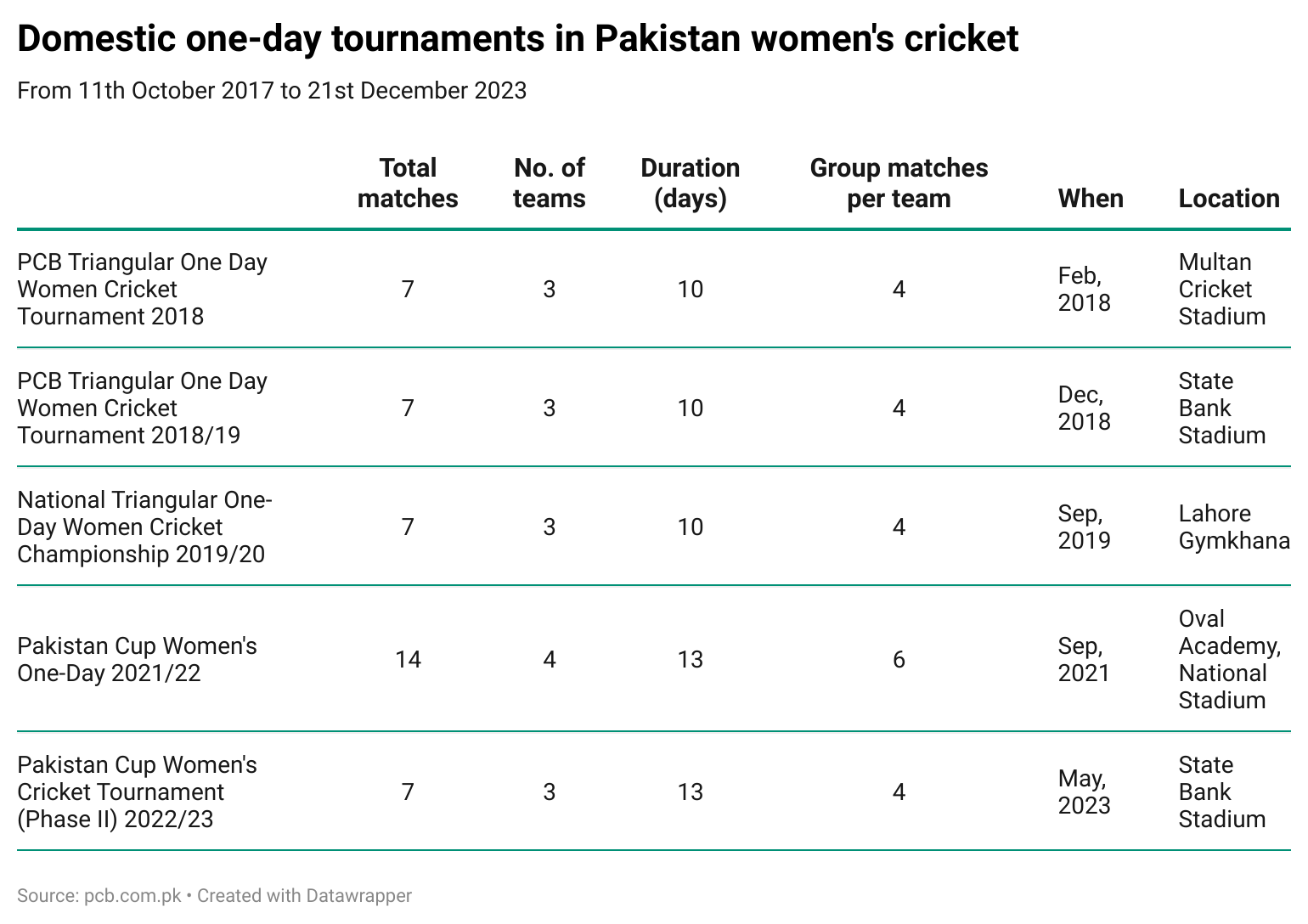

It doesn’t help that, from October 2017 to today, which makes up roughly 6 years or one and a half of an ODI championship cycle, we’ve only had 5 tournaments and 42 one-day matches scheduled, including finals and knockout games. For a country of nearly 120 million women, there are 3, sometimes 4, teams of 12 to 15 players playing one-day cricket every year.

We look at scorecards after ODIs and think about how every one of our “good” batting innings in international cricket takes at least one mammoth carry job. We want Sidra Amin to bat us to glory time after time after time. We wonder why Muneeba Ali isn’t converting her starts despite being one of our best domestic performers. But Sidra, in nearly 13 years of playing senior-level cricket, has played just 65 domestic one-dayers, while Muneeba, in nearly 8 years, has played only 42 domestic one-dayers. And these 2 are still some of the lucky ones, as they played back when the 17-team Mohtarma Fatima Jinnah National Women Cricket Championship was around. For the newer players, all they know is a life where you get between 4 to 6 one-day matches a year – or none at all, as it was for the players selected for the Emerging Asia Cup this year.

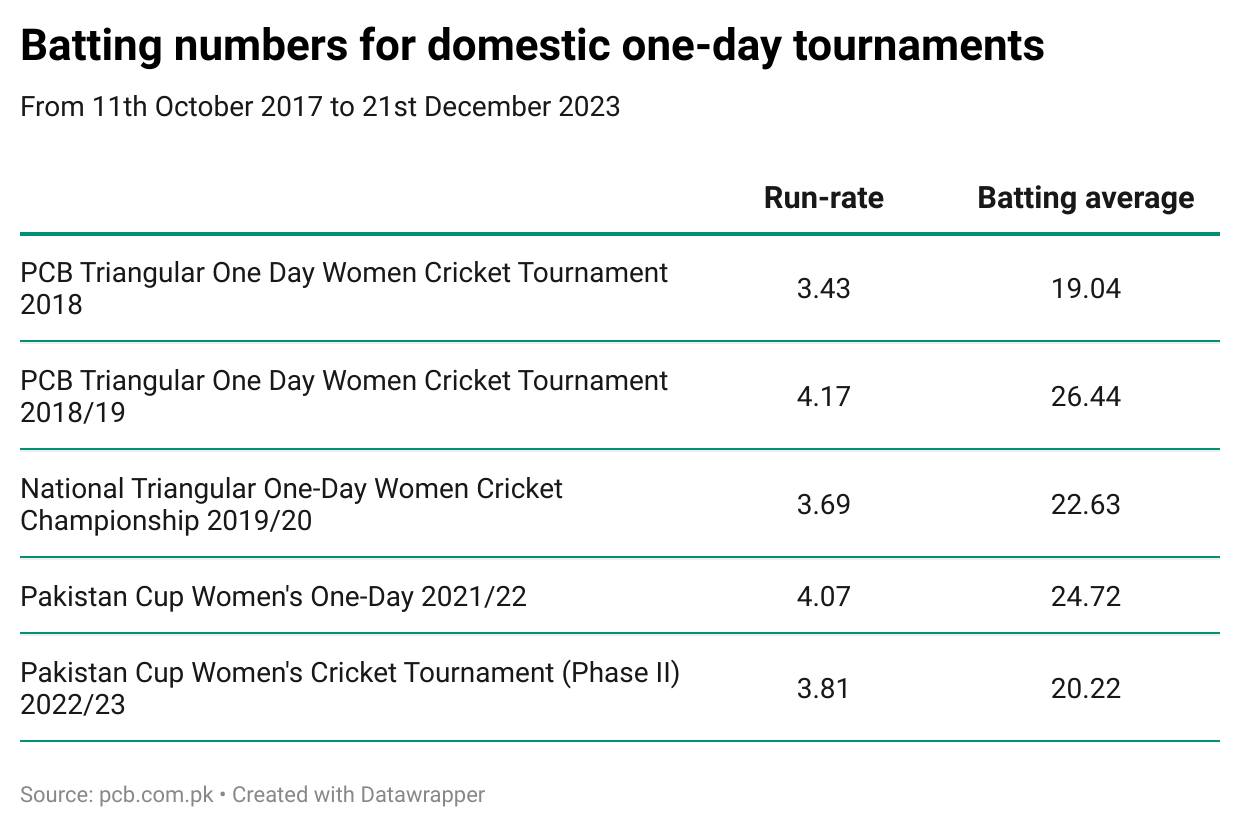

Is it a surprise, then, with these few opportunities, that even at the domestic level, our one-day numbers are disappointing? That the highest tournament run rate we’ve seen in the past 6 years is just 4.17 RPO, back in December 2018? That we’ve only had 6 centurions in this time? That teams have scored 200+ just 14 times in 82 attempts across all these domestic tournaments? That bowlers, particularly spinners, have been able to take advantage of slow pitches and undercooked batting lineups and then run rampant against them?

Is it a surprise, then, that our batters, with a handful of List A games every year and rarely (if ever) experiencing the art of building a proper ODI innings at the domestic level, cannot outperform their opponents in international cricket? That they score fewer runs and score them slower versus international bowlers who come from countries where they toil hard in red ball and one-day cricket? Is it a surprise that our bowlers, when put up against experienced betters who play the conditions well, struggle to come good after playing on pitches where wickets were far easier to come by than runs?

Take a look at the batting numbers and bowling numbers for the last 5 one-day tournaments we’ve had.

You’ll notice the numbers back what I’ve said: spin dominates our domestic cricket, and it’s not just because we have more of those than pacers. It is because spinners are rewarded, both by pitches that suit them and by the batters who can’t seem to play them out or score against them. This, in turn, means our spinners’ numbers look better than they perhaps should, but it means even worse news for our batters. In fact, look at the batting numbers, and you’ll see the run rate and averages are worse than our team’s numbers at the international level.

How does that even happen? How does a system see its batters do worse at domestic level versus domestic level bowlers than at international level versus international level bowlers?

Some may argue it’s because we’ve got a lot more depth in bowlers than we have in batters, that our “domestic level” bowlers are actually quite good. And sure, our bowlers are quite good; we have a good amount of depth, especially in spin options.

But I’d argue they’re looking at it wrong.

We fare worse at the domestic level, not just because of the great depth in our bowling but mostly because of the lack of depth in our batters. Beyond our national team’s batters, who get to experience world-class bowlers on tours and learn how to play and play them well over the years, the domestic batters struggle to come even close to those up top. They struggle to build innings, make high scores, or put in match-winning performances. And so, tournament after tournament, we have the same batters — Aliya Riaz, Nida Dar, Sidra Amin, Bismah Maroof, Muneeba Ali — taking turns topping the charts. And even their rather slow-starting careers – impressive, but still slow-starting – show that batters that progress from our system to the international level take a significant time to settle in and become consistent run-scorers.

In our T20 domestic tournaments, the gulf between domestic and international level players is not as massive. This is why, when Nida Dar needed a new ODI opener a few months ago, she did not turn to a domestic one-day performer because, frankly, all the worthy batters were in her team already. Instead, she turned to T20 prodigy Shawaal Zulfiqar, who had played a grand total of 6 one-day matches at the time, and those too in 2021 when she was 16 years old. She’d come good in domestic T20s over the years, topping the run charts often (you can read more about her here), but she was not considered a one-day batter – not yet, at least.

That experiment didn’t end up working out for obvious reasons. But there is a lesson in there nonetheless: the domestic system isn’t doing its job. It isn’t developing the ODI players we need. And so the system must change.

What you must do, PCB, is as follows:

- Book main stadiums for tournaments

- Ensure there are better, proper ODI pitches that allow for run-scoring but also reward disciplined bowlers

- Increase the number of teams (six, at the least)

- Increase the number of matches

- Fix a domestic season into our yearly calendar

- Introduce one-day tournaments at the U19 and U16 levels so that the players that emerge have strong foundations

- And maybe someday, introduce two-day and three-day cricket too, so that our players learn much, much more about working for wickets and racking up runs

So do it, please. I’ve shown you where we stand, and I’ve suggested to you what we need. I hope this helps. Feel free to write back. Or not. And if you do end up doing any or all of the above, I may or may not take credit. Also, please stream the domestic tournaments online or on TV.

Thank and kind regards,

A long-suffering Pakistan women’s cricket fan

Leave a Reply